This book review comes to us thanks to guest contributor Carter Moon. Check out his Substack here!

No other book I’ve read this year has humbled me quite like Abolish Rent. Written by Tracy Rosenthal and Leonardo Vilchis, the book is a reflection on a decade of building the largest tenant union in the US and a manifesto advocating for permanently ending the commodification of housing. LA is arguably the American city most dominated by real estate interests; by taking on the landlord lobby the way that the LA Tenants Union (LATU) has been able to, they have faced down the beast in its most potent form. The book is really most instructive in how it teaches the reader to think about unionism. It’s a guidebook for how they’ve built a member-driven union where the tenants themselves decide the actions they want to take advocating for the right to stay in their homes. It forcefully rejects much of the conventional wisdom about electoral politics, traditional labor unions, and nonprofit legal advocacy. Few books have made me step back and reassess my own analysis of LA politics and where I put my organizing attention.

I personally have been a paper member of LATU since 2018, meaning I pay $5 a month in basic membership dues, but don’t otherwise organize with the union. I’ve always found their analysis and positions to be on point, and the diversity of tactics they use to defend tenants from particularly scummy landlords is really admirable. They’ll use the legal system to fight evictions when it seems like a good avenue, but they’ll also organize a whole building to go on rent strike to protest unacceptable living conditions or awful evictions; sometimes they’ll go with the tenants directly to their landlord’s front door to confront them in person. They conceive of rent as an unjust burden and a transfer of wealth from the working class upwards to a small minority of landlords, the bourgeoisie. They’ve stopped evictions, forced landlords to make repairs, and even got the city of LA to agree to buy a building where a landlord wanted to increase the rent by 300%.

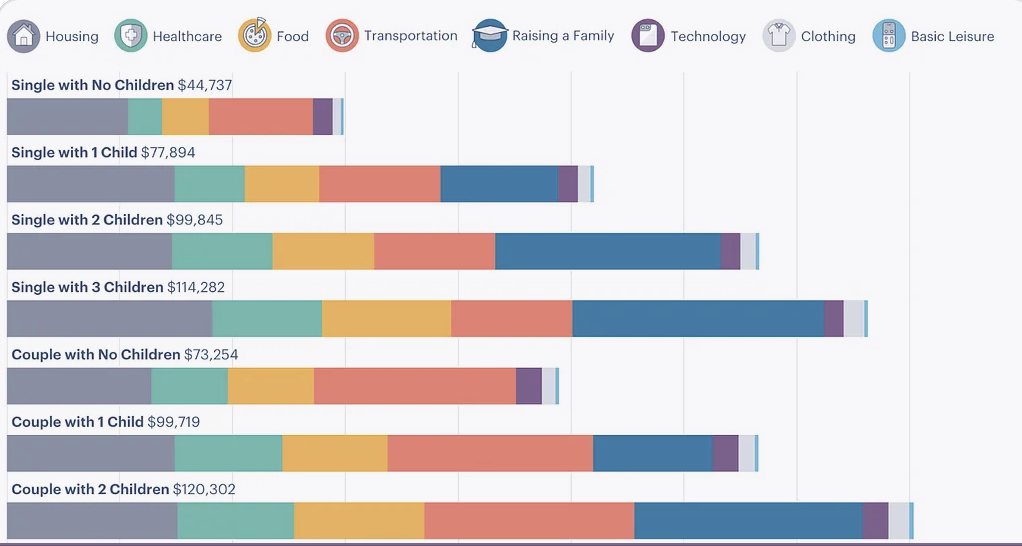

Rosenthal and Vilchis are crystal-clear in explaining why organizing against landlords in the United States is so essential: “Half of the 100 million tenants in the country—22 million tenant households—spend more than a third of their income on rent. A quarter spend over half of that income.” If you’ve ever had to spend more than a third of your paycheck on rent, you know how miserable it is. How impossible it feels to keep your head above water and save any money at all for emergencies. It’s easy to feel isolated and ashamed for not making enough to afford rent, and it’s only when you start to organize with other tenants that you realize you’re not alone, that you belong to a class of people who are being similarly exploited. A new report by the Ludwig Institute for Shared Economic Prosperity suggests that 60% of Americans can’t afford the basic costs of living, and housing is the largest contributing factor in that. Rosenthal and Vilchis emphasize:

“The frame of ‘housing crisis’ trains our attention away from the fundamental power imbalance between landlords and tenants … It encourages us to think about abstract, interchangeable ‘housing units’ and not about power, or about people and the constraints that shape their lives.”

The capitalist state as its currently formed in the US is incredibly bad at trying to patch over this crisis, as they explain: “The primary answer the state provides to the permanent crisis of housing is not public housing, owned and operated by the state, nor rent control, which regulates the amount of rent that private landlords can collect, but privately owned, publicly subsidized housing.” Cities, states, and the federal government already spend exorbitantly to fund housing, we just do it to the benefit of private capital rather than universal public good. It gets particularly perverse when you consider how much money we spend on criminalizing and warehousing the people who can’t afford the “affordable” housing we subsidize. (Rosenthal’s article in the New Republic on the Supreme Court’s horrific Grants Pass ruling is well worth reading on this subject.) We live in this absurd torment nexus of housing precarity that increasingly leaves even families with full-time incomes struggling to stay permanently housed, as Brian Goldstone explored in his book There Is No Place for Us.

I don’t want to center myself too much in this discussion, but the book really has made me reconsider how I’ve spent my years living in Los Angeles as a volunteer organizer. I’ve devoted the majority of my attention to migrant solidarity work, anti-carceral organizing, and campaigns to get left-progressives on the city council. I’ve always known I disagreed with LATU about the importance of getting allies elected to the council, but Abolish Rent has really made me reconsider my emphasis on that strategy. They quote Paulo Freire perfectly: “Attempting to liberate the oppressed without their reflective participation in the act of liberation is to treat them as objects that must be saved from a burning building.”

The city council electoral movement has, in some ways, attempted to side step this reality. There’s really no replacing the need for working class people to be in the driver’s seat of transforming our political economy themselves. No amount of winning municipal elections alone will accomplish that if people aren’t organized to demand what we need; as they emphasize, “You only get what you’re organized to take.” So much of the organizing work I’ve personally done in LA has in some ways attempted to sidestep this reality, and I recognize the need to pivot my own work accordingly.

What particularly moved me reading the book was a section in the fourth chapter about keeping the faith. They talk about rituals of protest and community building, which are ultimately acts of transformative faith. “Already present in our actions is the seed of a different way of life. Call it faith, mística, spirit, or God: We claim that righteous abundance as ours in service of the exploited and the oppressed.” This conception sees solidarity and liberatory politics as a spiritual practice, as an act of faith that the future can be better than our present, even if we don’t personally live to experience it. They provide what I believe is the most crystal-clear definition of liberatory organizing: “Our doctrine is the agency of everyday people to change the conditions of their everyday lives.” I have very little faith in any institutions or any higher power, but I do believe in the unbreakable power of people to change their material conditions through their collective will.

If you’re interested in any type of deep-rooted, liberatory organizing, this book is essential reading. Their prose is often poetic, but never pretentious. It does not matter if you’ve never read another political text in your life; they meet readers of all backgrounds with grace. Yet the citations are the only syllabus you need to familiarize yourself with if you want to get properly steeped in radical literature. These are two people who have been doing thankless spade-work together for over a decade and only want to share their knowledge with you. Even if you don’t feel called to organize tenants, their key insights into how to transform the social metabolism of the world we share is invaluable.