Los Angeles City Council District 11, encompassing affluent Westside neighborhoods from Venice and Mar Vista up to Brentwood and Pacific Palisades, has emerged as a focal point in the city’s ambitious affordable housing plans under Measure ULA. The voter-approved initiative, also known as the “mansion tax,” imposes a steep transfer tax on high-value real estate sales to fund housing and homelessness programs. According to city data, no district has generated more ULA transactions than CD11, thanks to a flurry of luxury property sales in the Westside. And CD11 has generated $131M in mansion tax revenue, second only to CD5 with $163M. And yet, the Westside is grappling with surging housing costs, gentrification pressures, and vocal resistance to new affordable housing. This convergence highlights both the promise of Measure ULA and the obstacles slowing its impact in our community.

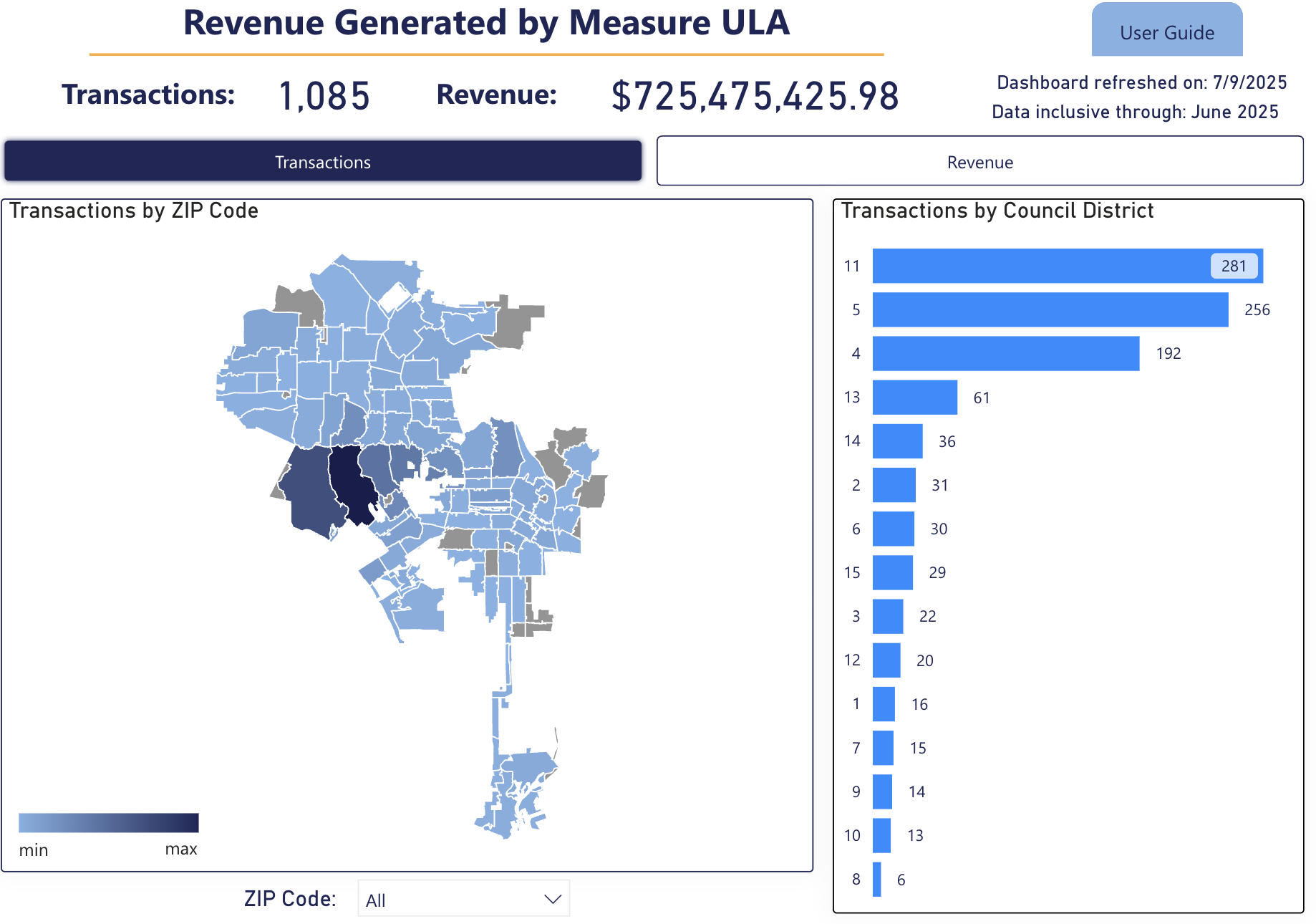

Los Angeles Housing Department (LAHD) dashboards reveal that Westside’s District 11 leads the city in high-end real estate activity subject to the ULA tax. From April 2023 (when the tax took effect) through June 2025, CD11 logged 281 property transactions over the $5 million threshold – the most of any council district – generating approximately $131 million in ULA revenue. That sum represents roughly 18% of all ULA funds collected citywide. By comparison, the only other district in the same league was the neighboring District 5, which saw 256 luxury sales but edged out CD11 in dollar volume with about $163 million. These figures underscore how heavily Measure ULA’s coffers rely on the Westside’s booming property market. Multi-million-dollar home sales in beachside communities like Venice, Brentwood and Pacific Palisades have effectively made CD11 the single largest contributor of “mansion tax” revenue in Los Angeles. City leaders once projected ULA could raise $600 million to $1 billion per year for housing initiatives, but the actual intake has been more modest – roughly $662 million in total through April 2025, partly due to a slowdown in luxury sales after the tax’s enactment.

Still, Westside real estate has remained a cash cow for the measure. The spike of big-ticket transactions just before ULA took effect and steady activity since then in CD11’s coveted neighborhoods have filled city accounts with hundreds of millions intended for affordable housing investments. And the totals could climb even higher. In July 2025, a sprawling Brentwood estate hit the market for $70 million—one of the most expensive listings in Los Angeles this year. If it sells at asking price, the sale would trigger a Measure ULA transfer tax of roughly $3.5 million for the city’s affordable housing fund.

Ironically, the Westside communities generating these funds are also among those most in need of affordable housing solutions. In neighborhoods like Venice and Mar Vista, median rents and home prices have soared to extreme heights, driven by affluent buyers and high-end development. Longtime lower-income residents have been increasingly priced out, and even middle-class Angelenos find it nearly impossible to afford Westside housing due to ongoing gentrification and displacement. Housing advocates say that while there is an urgent need for affordable housing on the Westside, local production has lagged far behind other parts of the city.

Multiple studies and city reports point to a troubling imbalance. Affordable housing developments (especially those for low-income and formerly homeless residents) have been concentrated in L.A.’s poorer neighborhoods, while wealthier districts like those on the Westside have built very few. A 2018 analysis by city officials found that “most affordable housing in the pipeline was being built in low-income neighborhoods with already stretched resources,” and identified high-resource Westside council districts as having ample land zoned for housing but precious few projects for the unhoused. In other words, the areas with the highest property values and tax contributions have historically done little to incorporate affordable units, leaving a dearth of low-cost housing in places like Venice, Brentwood and Westchester. This dynamic exacerbates displacement: as new luxury developments proliferate and rents climb, lower-income families and long-term renters are forced out, often with nowhere in the community they can afford to go.

City leaders and experts have warned that the Westside’s housing crisis is at a breaking point. Neighborhoods in CD11 have seen double-digit percentage rent hikes over the past few years, and modest bungalows are giving way to multimillion-dollar homes. The LA Times Editorial Board noted that CD11 is “a well-resourced area of the city where there is little permanent housing for low-income and homeless individuals and families,” bluntly concluding that “the Westside needs all the affordable housing it can get”.

Standing in stark contrast to the documented need, however, is fierce political and community opposition to affordable housing within District 11. That resistance is personified by the area’s City Council representative Traci Park, who campaigned in 2022 on a platform highly critical of transitional housing projects in her district. Since taking office, she has aligned with residents who strongly oppose affordable developments in their neighborhoods.

One flashpoint is the proposed Venice Dell mixed-income housing project, slated to bring 140 units of affordable and supportive housing to a city-owned parking lot near the Venice canals. Despite the project’s potential to house formerly homeless Angelenos in the heart of CD11, it has faced intense pushback from some Venice stakeholders and from Park herself. Park has been a longtime opponent of the plan, at one point publicly declaring the project “dead” and she even introduced a motion in City Council seeking to downsize or relocate it.

While political battles play out on the ground in CD11, citywide implementation of Measure ULA has also been sluggish, largely due to legal challenges. Opponents of the “mansion tax,” including real estate interests and taxpayer associations, filed lawsuits soon after voters approved the measure in 2022. A federal lawsuit was dismissed on jurisdictional grounds in 2023, and a state case brought by the Howard Jarvis Taxpayers Association was dismissed later that year. But appeals and repeal campaigns have continued, keeping uncertainty alive.

That legal limbo had real consequences: the city was reluctant to spend the money, fearing it might have to return funds if courts struck down the tax. Just this month, the City Council approved a new plan to spend nearly $425 million in ULA funds on expanded programs, including social housing and new construction. With lawsuits increasingly resolved and a clearer legal landscape, those funds may finally begin reaching communities like the Westside.

The contrast between CD11’s outsized contribution and its resistance to affordable housing has sparked debate about fairness. Housing advocates argue the revenue generated in CD11 should be reinvested here, in new affordable homes and renter protections. This dynamic has raised questions about whether the city’s approach to ULA implementation is consistent with its obligations under the federal Fair Housing Act. The law requires jurisdictions not only to avoid discrimination but to affirmatively further fair housing by expanding access to high-opportunity neighborhoods. If Measure ULA funds continue to be disproportionately invested in low-income areas while Westside communities resist new affordable housing, some advocates warn that the city could be at risk of violating its fair housing duties. The contrast between where the money is raised and where the housing is built, they argue, may perpetuate patterns of segregation and exclusion—precisely what the Fair Housing Act was designed to prevent.