Photographs and primary documentation for this article were provided by Peggy Lee Kennedy.

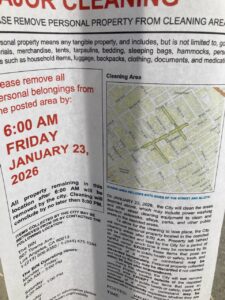

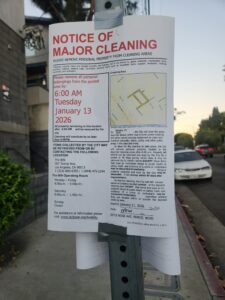

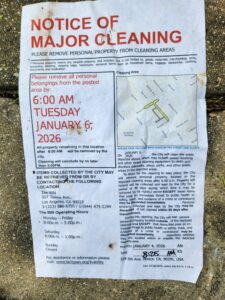

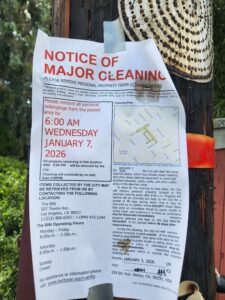

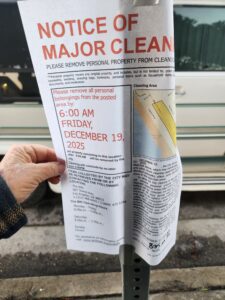

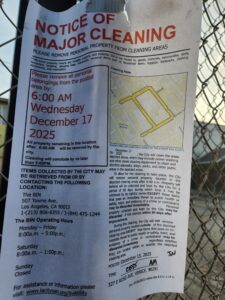

For months, residents and outreach volunteers in Venice have been documenting a pattern that is impossible to ignore. Notices posted block after block, often on the same road less than three days apart . . .

Sweeps carried out again and again. Police and sanitation crews clearing small encampments while people hurried to gather everything they owned . . .

Tents pushed from commercial corridors deeper into residential streets like Hampton Drive, then pushed again.

And on February 5, a man known locally as Paul was found dead on Hampton. Paul’s body is pictured below, lying lifeless on the sidewalk under a white sheet.

People who have been tracking the sweeps say Paul had been displaced repeatedly in the weeks leading up to his death. Outreach workers and public health researchers have warned for years that this kind of constant displacement carries severe risks. When people lose medications, lose contact with services, lose shelter from the elements, and are forced to move again and again, health conditions worsen. People become more vulnerable to violence, exposure, and untreated illness. Death is not an unpredictable tragedy under these conditions. It is a foreseeable outcome.

What has been happening in Venice is not random. It reflects a sustained policy direction.

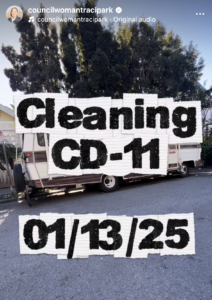

Since taking office, Councilmember Traci Park has introduced or supported at least nine separate motions creating or expanding enforcement zones under Municipal Code Section 41.18, each one adding new locations where unhoused people can be cited or forced to move. At the same time, more than a dozen resolutions restricting oversized vehicle parking have expanded the areas where people living in RVs or vans can be towed or displaced, even though those vehicles often represent the last form of shelter people have. Other motions have sought to accelerate towing and destruction of RV homes altogether.

These policies have unfolded in the absence of basic alternatives. The Westside entered this winter with effectively no local winter shelter beds. During severe winter storms, residents and advocates spent hours calling for emergency placements only to be told vouchers were exhausted and shelters were full or unavailable, leaving people outside in heavy rain, including elderly and medically vulnerable residents.

Meanwhile City leaders including Councilmember Park, Mayor Bass and City Attorney Feldstein Soto have actively blocked solutions that could change these conditions have been . The Venice Dell project, which would create deeply affordable and supportive housing on city owned land in Venice, has remained stalled for years while the city has spent public funds on litigation related to the project. The result is a landscape where enforcement expands faster than housing, and displacement becomes the primary tool of policy.

Researchers have documented what this approach produces. A UCLA Luskin study of CARE+ operations in Council District 11 found that sweeps typically function as displacement efforts rather than pathways to housing, with most unhoused residents simply pushed from one block to another. A RAND longitudinal study found that official homelessness counts are missing a large share of people living outdoors in areas like Venice, in part because displacement makes people harder to find, harder to count, and harder for outreach teams to reach. Other RAND findings show that reductions in visible homelessness in Venice have been driven largely by vehicle bans rather than housing placements, while the number of people sleeping completely unsheltered has risen.

These findings match what residents have seen with their own eyes. Notices posted repeatedly on the same streets. Large enforcement deployments clearing small encampments. Physical barriers installed to prevent people from returning. Tents appearing deeper in neighborhoods because there is nowhere else to go.

To understand what this means, it is necessary to talk about something deeper than policy mechanics. It is necessary to talk about dehumanization.

Civil rights organizations and homelessness advocates have warned that the constant portrayal of unhoused people as nuisances, hazards, or trash to be removed creates the conditions for violence and neglect. When people are treated as obstacles to be cleared rather than human beings to be helped, it becomes easier to accept policies that knowingly place them in danger.

But dehumanization does more than harm the people directly targeted. It changes everyone else, too.

Policies like repeated sweeps and exclusion zones do not just remove people from view. They condition the public to accept the unacceptable. Each time a tent is cleared without housing, each time belongings are thrown away, each time a human being is treated as a problem to be managed rather than a neighbor to be helped, the line of what feels normal shifts a little farther.

What would once have shocked us becomes routine. What once would have been called cruelty is rebranded as cleanliness, safety, or order. And over time, people stop seeing the human beings at the center of it at all.

This conditioning does not happen only through policy. It also happens through imagery.

On social media, enforcement operations are often presented as scenes of order being restored: piles of belongings being cleared, sanitation crews washing sidewalks, vehicles being towed away. These images are framed as evidence of success, proof that a problem has been removed. But what is actually being removed is not debris. It is the last shelter and possessions of human beings.

This imagery matters because it shapes how the public understands what is happening. When the camera lingers on bags and tents but not on the people who owned them, when a towed RV is shown without acknowledging that it was someone’s home, the message is subtle but powerful. It teaches viewers to see the objects first and the people last, or not at all.

Over time, repeated images like these can normalize the idea that clearing people away is a public good in itself. They make displacement appear routine, even necessary, rather than extraordinary and harmful.

Each time we see a post celebrating a sweep or a tow, it should give us pause. We should ask what happened to the people who were there the day before, and where they were supposed to go. We should ask what it means for a society to take pride in removing its most vulnerable members from view.

And we should ask a harder question as well: once we accept the removal of one group of people as normal, who will be next to be treated that way?

History shows that this process is not confined to one group. Again and again, in different countries and different eras, governments have begun by targeting people who were already marginalized, people who could be portrayed as burdens, outsiders, or threats to public order. Once the machinery of exclusion was built and normalized, it did not remain limited to its first targets. The category of who could be treated as disposable expanded.

That is why so many scholars, civil rights organizations, and historians warn about the danger of dehumanizing language and policies, even when they are first directed at the most vulnerable. What begins with people sleeping in tents can end with far broader attacks on civil liberties and human dignity.

Across the country today, political leaders are openly calling for detention camps, mass removals, and the criminalization of entire categories of people. These proposals do not appear overnight. They grow in a political culture that has already been conditioned to accept the removal of human beings as routine.

What is happening in Venice is part of that larger trajectory.

Death is not an unintended side effect of policies that knowingly expose vulnerable people to hunger, cold, illness, and displacement. It is the natural and foreseeable result. When survival itself is criminalized and shelter is unavailable, the outcome is written in advance.

Paul’s death is not an isolated tragedy. It is a warning.

It is a warning about what happens when a society begins to treat some of its members as refuse to be cleared from view for the comfort of others. It is a warning about what happens when policy replaces compassion with punishment, and housing with handcuffs.

And it is a warning about where this path leads if it is not stopped.

Communities must say no to laws that criminalize homelessness instead of solving it. No to policies that seize the last belongings of people who have almost nothing. No to detention camps and forced removals masquerading as public safety. No to the normalization of language and policies that treat human beings as disposable. And no to the broader authoritarian politics that seek to expand these practices nationwide.