The City of LA just paid roughly $1.8 million to Gibson Dunn for just 13 days of work in the L.A. Alliance homelessness case, records show. The firm, brought in a week before a high-stakes federal hearing, assigned at least 15 attorneys billing roughly $1,300 an hour. The bill blew past a $900,000 spending cap approved by City Council in a matter of days, just after City Hall approved massive layoffs due to a nearly $1-billion budget shortfall.

This out of control spending on outside legal bills comes after U.S. District Judge David O. Carter found the City out of compliance with a 2022 settlement requiring 12,915 beds or housing placements by June 2027. Carter appointed a third-party monitor to verify the City’s claims. But instead of investing in placements, case management, or the verified data systems the court now demands, the City spent an average of $140,000 a day on outside counsel.

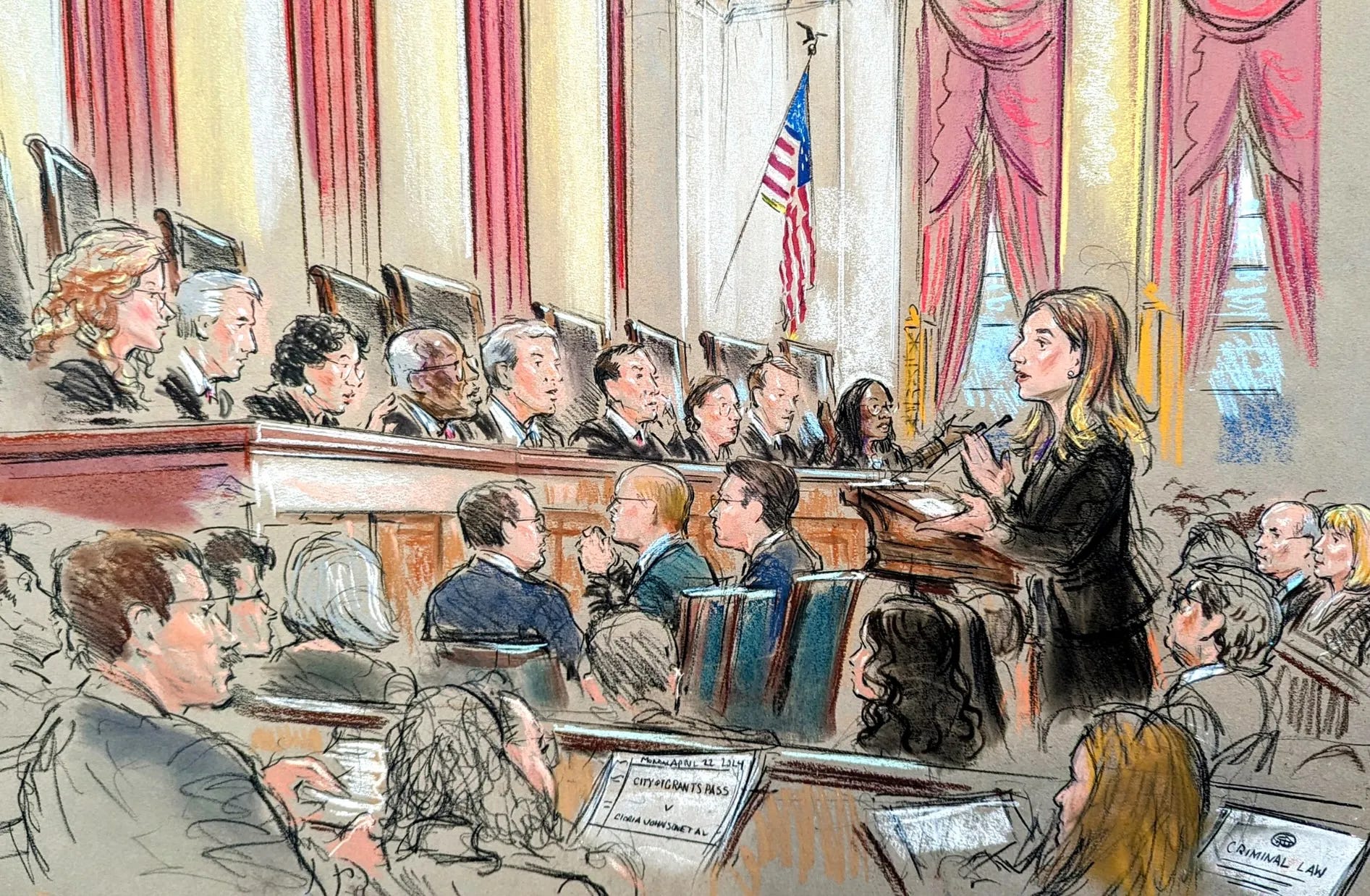

The choice of Gibson Dunn is significant. The firm was behind the landmark Grants Pass case at the U.S. Supreme Court, a ruling that has become a national turning point in homelessness policy. The decision gave cities the green light to enforce anti-camping bans, even when adequate shelter is unavailable, undermining proven housing-first strategies in favor of punitive approaches that push unhoused people out of public view rather than into stable housing. Its Supreme Court track record also includes two landmark cases that changed American politics. Ted Olson of Gibson Dunn led George W. Bush’s legal team in Bush v. Gore, which stopped the Florida recount and effectively decided the 2000 presidential election and also argued Citizens United, the 2010 ruling that opened the door to unlimited corporate spending in elections.

The firm has also been on the winning side of other high-profile, controversial cases. In Wal-Mart v. Dukes, it persuaded the Supreme Court to block what would have been the largest gender-discrimination class action in U.S. history. Earlier this year, Gibson Dunn secured a $667-million jury verdict against Greenpeace in a case brought by the Dakota Access Pipeline operator, a judgment civil-liberties groups say will chill protest. The Montana Supreme Court once upheld millions in punitive damages against the firm in a malicious-prosecution case, describing its tactics as “legal thuggery”.

Los Angeles already has a system for hiring outside counsel when the City Attorney’s office has a conflict, with hourly rates a fraction of Gibson Dunn’s and budgets overseen by the City Administrative Officer. In this case, the City bypassed that lower-cost channel, paying corporate-law-firm rates to fight court oversight in a case it is already losing.

This arrangement raises more than fiscal questions. The City Council had instructed the City Attorney to report regularly on the spending in this litigation, a directive she ignored when Gibson Dunn’s bill blew past the cap. This raises concerns about a breach of her ethical duty to her client, the City of Los Angeles. Adding to the conflict, campaign finance records show that Hydee Feldstein-Soto received thousands of dollars in contributions from Gibson Dunn partners toward her 2022 election.

City officials may claim they are protecting democratic control over homelessness programs by fighting receivership, but funneling public money to a private firm with no meaningful oversight is itself antidemocratic. Hiring a firm known for Grants Pass, Bush v. Gore, Citizens United, and Wal-Mart v. Dukes to fight stronger court oversight sends a clear signal: preserving political control takes priority over meeting the court’s order to deliver beds and housing placements, even when that control is exercised behind closed doors and shielded from public accountability.

Carter stopped short of appointing a receiver, which would have shifted operational control to a court-appointed manager with the power to hire, change contracts, and seek waivers from rules that impede compliance. Instead, he chose a monitor, who will audit and report while the City retains management, at least until the next compliance review. Receivership remains on the table if progress stalls.

The $1.8 million spent in May could have funded library hours, animal-shelter staffing, outreach teams, or interim housing. Instead, it bought two weeks of legal work from a firm whose recent victories have empowered criminalization and corporate power. The City Attorney’s ability to double a spending cap in days without timely notice to the Council raises basic questions about fiscal responsibility and accountability.

Some councilmembers are now demanding a full public accounting. Advocates are calling for reforms, including publishing all invoices, requiring Council votes before outside-counsel caps are exceeded, and fast-track hiring and procurement for homelessness programs so money turns into services quickly. If the monitor’s reports show continued noncompliance, the court could appoint a narrowly focused receiver to deliver the outcomes the City promised, and return control only once those outcomes are real.

Voters may also decide whether the City Attorney, whose tenure since 2022 has been marked by a series of reckless choices, should remain in office after spending $1.8 million in less than two weeks to fight oversight in a losing case.