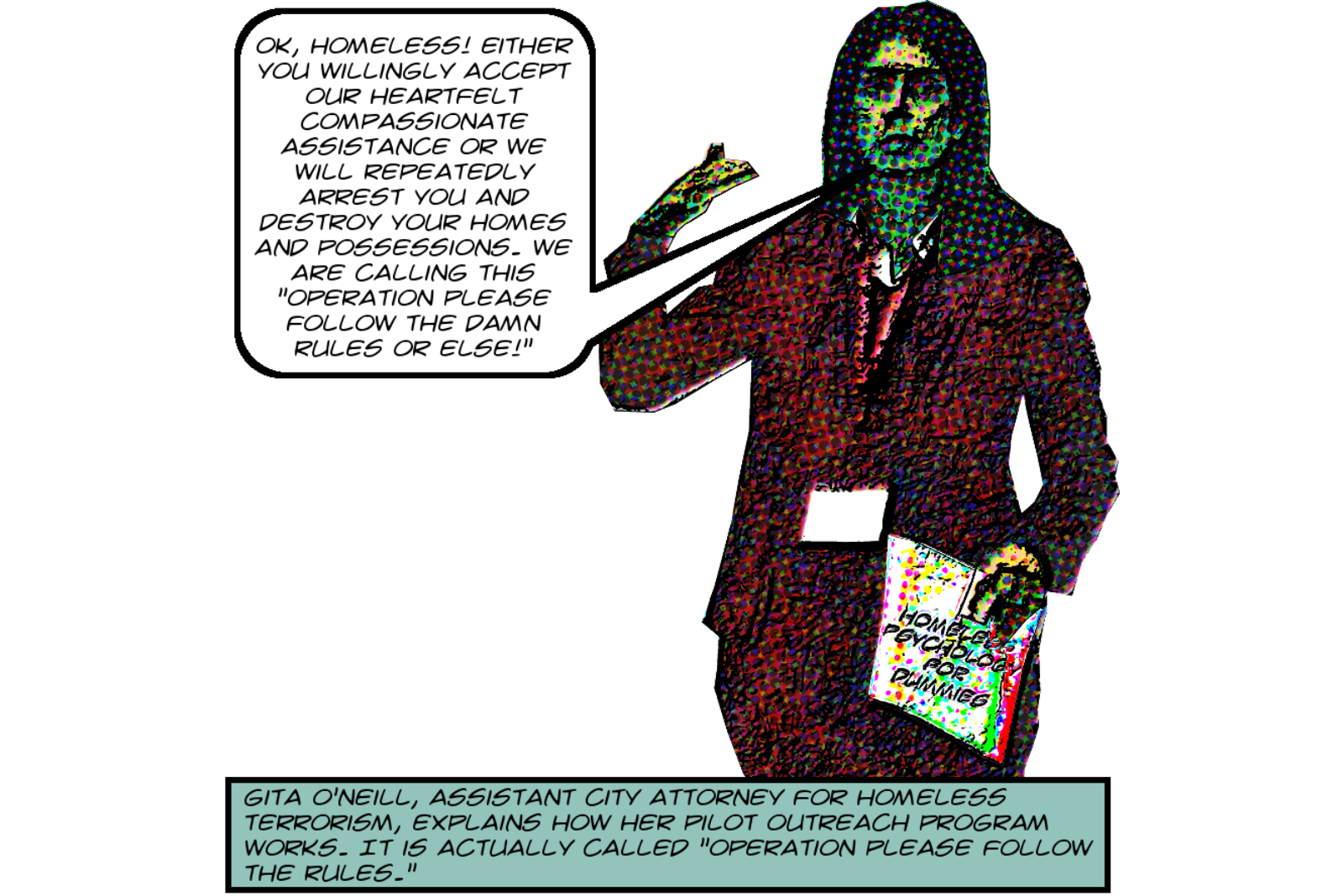

(Image thanks to michaelkohlhaas.org)

In a move that has alarmed civil rights advocates and service providers, the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority (LAHSA) is poised to appoint longtime City Attorney official Gita O’Neill as its interim CEO. The LAHSA Commission is expected to vote Friday on O’Neill’s one-year contract, which comes as the embattled agency faces a loss of funding, internal scandals, and growing pressure to align with law enforcement strategies in the wake of a landmark Supreme Court decision.

O’Neill has spent more than two decades in the Los Angeles City Attorney’s office, where she became best known for her role directing the Neighborhood Prosecutor Program and later leading homelessness policy. In those roles, she helped shape and enforce anti-homeless ordinances like LAMC 41.18, which prohibits sitting, sleeping, or storing belongings in designated “sensitive” areas. Her work has long been closely tied to law enforcement responses to visible homelessness, particularly in gentrifying neighborhoods like Venice.

But O’Neill’s influence extended beyond policymaking. Public records obtained by the watchdog blog Michael Kohlhaas dot org show that she played an active role in coordinating encampment sweeps with LAPD, sanitation workers, and business interests. In a series of internal emails, O’Neill communicated with property owners, city departments, and law enforcement to facilitate “Operation Healthy Streets,” an enforcement-heavy campaign targeting unhoused people in Skid Row. In one exchange, O’Neill even encouraged a business owner to install hostile landscaping as a means of displacing sidewalk dwellers.

The emails also reveal efforts to condition access to services on compliance with enforcement, blurring the line between care and coercion. These records offer a rare window into how the City Attorney’s office under O’Neill worked behind the scenes to criminalize homelessness through administrative and physical displacement tactics. Activists point out that her work helped formalize the architecture of punitive homelessness policy in Los Angeles.

John Raphling, a senior researcher at Human Rights Watch and former Los Angeles public defender, said O’Neill has “helped create the Neighborhood Prosecutor Program, ” a system that weaponizes law enforcement tools to respond to the demands of wealthy property owners rather than the needs of unhoused residents. “Their job is to respond to neighbor complaints, and their primary tools are criminalization and sweeps,” he explained. “The idea that someone who’s run that program would now be in charge of LA’s largest services agency is troubling.”

Peggy Lee Kennedy, co-founder of the Venice Justice Committee, echoed those concerns. She noted that O’Neill worked alongside other City Attorney officials to rewrite anti-homeless laws like LAMC 41.18 and 56.11 in ways that made them harder to challenge in court, even after prior versions had been ruled unconstitutional. “They weren’t trying to make these laws more just,” Kennedy said. “They were trying to make them harder for civil rights attorneys to fight.” The goal of these legal revisions, Kenney explained, was not justice but insulation from legal challenges.

While it’s possible O’Neill has contributed to programming within the City Attorney’s office such as diversion initiatives, both Raphling and Kennedy emphasized that the core of her career has centered on prosecution and legal enforcement, not delivering housing or running service programs. They argue that placing a career prosecutor in charge of LAHSA is a fundamental betrayal of the agency’s central mission, which is supposed to be housing-first, trauma-informed, and rooted in care.

The timing of the appointment has also raised eyebrows. LAHSA is undergoing a dramatic downsizing after Los Angeles County decided to pull nearly $350 million in funding and move hundreds of staff and programs to a new Department of Homeless Services. The City of Los Angeles is now LAHSA’s primary funder, and the agency is under pressure to demonstrate more “accountability” and visible results. Some worry O’Neill’s appointment is a political concession meant to reassure City Hall that LAHSA will now support a tougher stance on encampments and compliance.

The agency’s credibility has already been eroded by recent scandals. Over the past year, LAHSA has faced whistleblower allegations of misconduct, including retaliation against staff, destruction of public records, and manipulation of Inside Safe data to protect political leadership. Two former officials received an $800,000 settlement. Meanwhile, audits found that LAHSA lacked sufficient financial oversight and delayed payments to service providers. Just last week, LAHSA was caught quietly revising its 2025 homeless count to make the City’s numbers look lower—moving over 400 people from the City of L.A.’s tally to neighboring jurisdictions without explanation to elected officials.

Against this backdrop, the decision to appoint a prosecutor rather than a service professional has deepened distrust.

For Raphling, O’Neill’s appointment to lead LAHSA, at a moment when public agencies are under pressure to appear “tough on homelessness,” suggests that criminalization may take priority over care. Kennedy sees it the same way: the choice signals a pivot away from LAHSA’s public mission and a deeper entrenchment of punitive policies under the banner of reform.

The LAHSA Commission will vote Friday morning. Community groups are urging the public to speak out.