One year after the Pacific Palisades fire devastated entire neighborhoods, Los Angeles is confronting what the disaster revealed and what has gone unlearned since. Thousands of residents lost homes and livelihoods. Evacuations were chaotic. Infrastructure failed. The sheer scale of destruction forced uncomfortable questions about preparedness in a city increasingly shaped by climate-driven extremes.

That reckoning comes at a moment when climate denialism is no longer confined to the fringes. At the federal level, an extremist MAGA government has made hostility to climate science a defining feature, rolling back environmental protections, undermining federal agencies, and treating reality itself as a partisan inconvenience. In that context, cities like Los Angeles are supposed to serve as a bulwark, places where evidence, expertise, and long-term planning still matter. Instead, at a recent anniversary rally called They Let Us Burn, Councilmember Traci Park echoed the very rhetoric Los Angeles should be resisting.

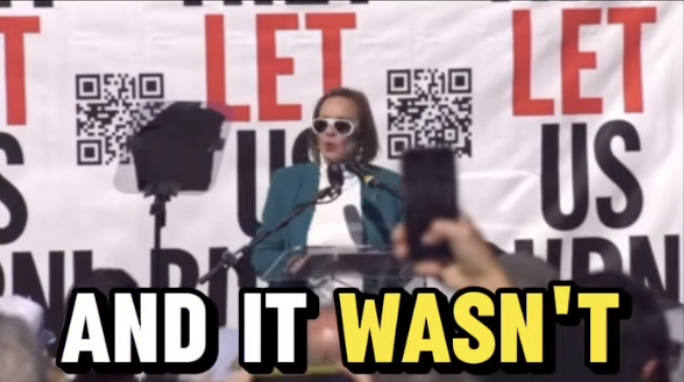

Speaking to residents still living with the consequences of the fire, Park insisted the Palisades disaster “wasn’t climate change, and don’t let anybody try to tell you otherwise.” The statement cut against overwhelming scientific consensus and against what climate experts have documented for years.

As Los Angeles Times climate columnist Sammy Roth has repeatedly explained, climate change does not need to strike a match to shape the outcome. Hotter temperatures, prolonged drought, and extreme wind events create the conditions in which fires spread faster, burn hotter, and overwhelm response systems. Denying that reality does not protect communities. It leaves them exposed.

Park’s remarks were especially striking because she represents the Pacific Palisades, one of the communities most severely affected by the fire. In the months since, she has positioned herself as a central figure in recovery efforts, advocating for infrastructure upgrades, emergency response improvements, and expanded resources for the Los Angeles Fire Department. But her refusal to acknowledge climate change as a driver of the disaster reveals a deeper pattern in her approach to governance: reacting to crises after they erupt while avoiding the underlying causes that make those crises inevitable.

That contradiction is evident in Park’s vocal support for a new ballot initiative launched by the union representing Los Angeles firefighters, which would raise the city’s sales tax by a half cent to fund new fire stations, hire additional firefighters, and purchase equipment.

“This is about preparedness,” Park said at the campaign launch on Thursday. “I, for one, cannot let what happened to my Pacific Palisades constituents happen to any other community.”

The proposed tax increase would generate more than $300 million annually for the Los Angeles Fire Department and could raise as much as $10 billion by mid-century. Union leaders say the department has been underfunded for decades, with staffing levels lagging far behind comparable cities and essentially the same number of firefighters as in the 1960s. Few dispute that LAFD needs sustained investment.

But Park’s embrace of the measure highlights a fundamental tension in her leadership. She is willing to raise taxes to fund emergency response while simultaneously denying the climate conditions that are making emergencies more frequent and more severe. Pouring hundreds of millions of dollars into fire suppression while rejecting climate reality is not a strategy to reduce disaster risk.

Roth has warned that this approach locks cities into an endless and costly cycle. If leaders refuse to acknowledge climate change, the only remaining option is to keep expanding emergency response, rebuilding after each catastrophe, and hoping the next one is not worse. That is not resilience but managed decline.

Park’s climate denial is not an isolated misstatement. It reflects a broader governing style that treats systemic crises as isolated incidents, to be managed through rhetoric and enforcement rather than structural change. In a city already under strain from federal backsliding, that approach is especially dangerous.

On homelessness, Park has consistently opposed or slowed affordable housing while promoting enforcement-led responses such as sweeps and vehicle-dwelling crackdowns. Rather than addressing the root causes of homelessness, a severe housing shortage and deepening economic inequality, her policies focus on visibility and removal. The result is displacement without resolution, pushing people from one neighborhood to another while homelessness grows more entrenched.

Her approach to public safety follows a similar pattern. Faced with issues like copper wire theft, Park emphasizes policing, surveillance, and crackdowns. These responses may create the appearance of action, but they leave untouched the underlying drivers of such crimes: poverty, housing instability, and economic desperation. When leaders refuse to engage those causes, enforcement becomes an endless and ineffective loop.

From climate to homelessness to crime, Park’s leadership is defined by reaction rather than prevention, denial rather than diagnosis. The Palisades fire should have been a moment of clarity and an opportunity for Los Angeles to affirm its role as a counterweight to national denial by committing to evidence-based solutions. Denying the role of climate change and repeating patterns of enforcement-only governance does the opposite.