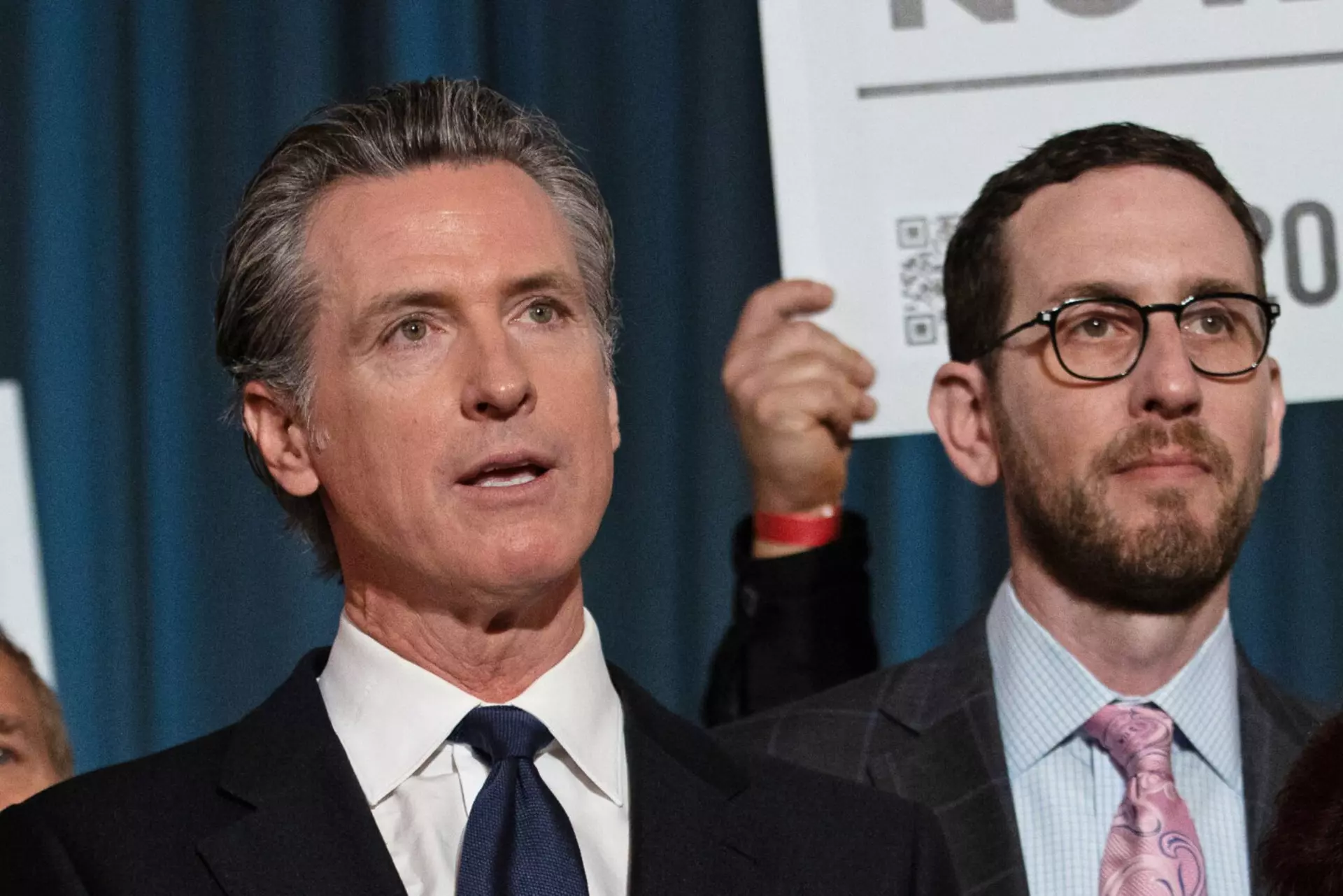

Governor Gavin Newsom has signed SB 79, one of the most significant housing reforms in California’s history, calling it a major step toward addressing the state’s long-running housing shortage. The law requires cities to allow mid-rise housing near major transit stops and imposes penalties on local governments that continue to block such projects.

After months of lobbying and last-minute amendments, SB 79 survived intense opposition from suburban lawmakers and local control advocates. It narrowly passed the Legislature and spent several weeks on the governor’s desk before Newsom signed it on October 10, alongside more than forty other housing bills.

The new law represents a major victory for the YIMBY, or “Yes In My Backyard,” movement, which has long sought to undo exclusionary zoning and restrictive land use rules. SB 79 builds on earlier reforms such as SB 35 and the Transit Oriented Communities program by legalizing apartment buildings up to five stories near state-designated transit corridors. Cities that fail to approve qualifying projects can face fines, a move that could have major consequences for Los Angeles, where the city has permitted only 13 percent of the housing units it needs to meet its state goals.

Opponents of the bill, including LA City Councilmember Traci Park, claimed that it would open the floodgates to overdevelopment, strain infrastructure, and threaten public safety in fire-prone areas. In public comments and interviews, Park argued that the law would override local zoning in neighborhoods like the Pacific Palisades. Housing advocates and state officials have repeatedly said those claims are false.

SB 79 applies only to parcels within a half-mile of major transit stops, which excludes most of the Palisades and much of the low-density Westside. It also exempts all very high fire-risk zones, a safeguard written into the bill after concerns from both firefighters and environmental advocates. In his signing message, Newsom specifically clarified that the bill does not override local control in areas such as Pacific Palisades, where there are no qualifying major transit stops.

For Mar Vista and similar neighborhoods, the law will not mandate any zoning changes. It may, however, make it easier for projects near existing bus and light-rail corridors like the Expo Line or Venice Boulevard to move forward without years of delay. These are areas that already have infrastructure, access to jobs, and frequent transit, the conditions the law was designed to prioritize.

The infrastructure argument has also been misrepresented. Developers already pay for upgrades, and denser housing produces more tax revenue per mile of road, pipe, and power line. Experts note that the city’s real problem is a fiscal one. Los Angeles struggles to maintain its infrastructure because it does not have enough housing or taxpayers to sustain its current footprint.

Mayor Karen Bass opposed the bill, arguing that it undermines local control, while its author, Senator Scott Wiener, said the law was necessary precisely because local control had failed. “Democrats need to be willing to say no to NIMBYs and to city councils that are yelling at them,” Wiener said earlier this year.

For Los Angeles, the passage of SB 79 could mark a turning point. It gives the state new tools to hold cities accountable for meeting housing goals and to push development toward transit-rich areas rather than wildfire zones and open space. While most of the Westside will remain untouched, the law will likely accelerate construction in key corridors that have long been slated for growth.