On Tuesday, August 5, LAPD’s Westside Division will host a “National Night Out” event at Mar Vista Park, in coordination with City Councilmembers Traci Park and Katy Yaroslavsky. While this is being billed as a family-friendly celebration of “community-police partnerships,” it’s anything but.

At a time when ICE raids are terrorizing immigrant communities across Los Angeles, this event is out of touch and dangerous. Immigrant neighbors are being forced to stay home, street vendors have disappeared from corners they’ve worked for years, and families no longer feel safe bringing their kids to local parks. In this climate, hosting a photo-op for police in the middle of a public park sends a clear message: our city would rather build public trust in the LAPD than protect the very people the department has a documented history of harassing, targeting, and killing.

At a time when ICE raids are terrorizing immigrant communities across Los Angeles, this event is out of touch and dangerous. Immigrant neighbors are being forced to stay home, street vendors have disappeared from corners they’ve worked for years, and families no longer feel safe bringing their kids to local parks. In this climate, hosting a photo-op for police in the middle of a public park sends a clear message: our city would rather build public trust in the LAPD than protect the very people the department has a documented history of harassing, targeting, and killing.

LAPD has not shown up for our communities in this moment of crisis. Instead, they have shared surveillance data with ICE, refused to intervene when federal agents detained workers and parents in front of their children, and deployed violent tactics against peaceful protesters calling for immigrant rights. Meanwhile, it is neighbors—not police—who are keeping our communities safe. It’s the people running street patrols to monitor ICE. It’s the mutual aid networks buying out vendors’ food so they can stay home without going hungry. It’s the friends and family delivering groceries, raising legal funds, and helping each other survive.

That’s what makes this year’s National Night Out at Mar Vista Park so deeply disrespectful. As LENS Magazine recently documented, this park is more than just a green space—it’s been a vital sanctuary for immigrant families on the Westside. It’s where children learned to swim, friendships were forged across borders, and new arrivals found connection in a city that can often feel alienating. For undocumented mothers, day laborers, and working-class caregivers, the park has been a rare space of safety and belonging. And yet now, in the midst of escalating ICE raids and mass fear, LAPD is staging a photo-op here, at the very place our neighbors once gathered for peace. The timing isn’t just tone-deaf. It’s cruel. Families are staying home, vendors are disappearing, and community members are being hunted. The same public park that once welcomed them now hosts the very police department that collaborates with ICE, shares surveillance data, and brutalizes protesters. Hosting National Night Out here sends a chilling message: this space is not yours anymore.

That’s what makes this year’s National Night Out at Mar Vista Park so deeply disrespectful. As LENS Magazine recently documented, this park is more than just a green space—it’s been a vital sanctuary for immigrant families on the Westside. It’s where children learned to swim, friendships were forged across borders, and new arrivals found connection in a city that can often feel alienating. For undocumented mothers, day laborers, and working-class caregivers, the park has been a rare space of safety and belonging. And yet now, in the midst of escalating ICE raids and mass fear, LAPD is staging a photo-op here, at the very place our neighbors once gathered for peace. The timing isn’t just tone-deaf. It’s cruel. Families are staying home, vendors are disappearing, and community members are being hunted. The same public park that once welcomed them now hosts the very police department that collaborates with ICE, shares surveillance data, and brutalizes protesters. Hosting National Night Out here sends a chilling message: this space is not yours anymore.

Every summer, police departments across the country roll out bounce houses, BBQs, and selfie booths for “National Night Out.” Marketed as a feel-good block party to “build police-community relationships,” this annual event is actually one of the largest coordinated copaganda efforts in the country.

National Night Out (NNO) began in 1984 as a national crime-prevention event with deep ties to law enforcement agencies. It was launched through a grant from the U.S. Department of Justice’s Bureau of Justice Assistance and organized by a nonprofit called the National Association of Town Watch (NATW). NATW itself had grown out of the 1970s neighborhood watch movement and was “a nationwide organization dedicated to . . . community-based, law enforcement–affiliated crime prevention activities.” In fact, NNO’s first incarnation was simple: neighbors were encouraged to turn on their porch lights and sit outside as a symbolic “take back the neighborhood” stance against crime. The inaugural Night Out in 1984 saw 2.5 million residents across 400 communities participate; by 2016 it had expanded to tens of millions in over 16,000 communities. What started as front-porch vigils soon evolved into block parties, cookouts, and even large festivals, all with the stated goal of fostering “police-community partnerships and neighborhood camaraderie.” Federal support was instrumental in this growth: the DOJ continued funding NNO into the 1990s, and participation swelled to over 32 million people by 1999. The visibility of the event also grew, with mayors, police chiefs, and even U.S. Presidents and Attorneys General regularly attending or endorsing local NNO gatherings.

Despite its friendly, grassroots branding, National Night Out was never a purely community-initiated affair. It was engineered as part of the 1980s push for community policing programs. Its organizer, NATW founder Matt Peskin, explicitly built on existing networks of neighborhood watch groups and police departments to roll out the first NNO. This meant that from the outset, police departments played a leading role in NNO planning and activities (many departments still organize the events each year). The close involvement of law enforcement shaped NNO’s core message: that public safety is a shared responsibility between “good neighbors” and the police. In practice, this often translated into neighbors acting as the eyes and ears of the police, an extension of the neighborhood watch ethos. DOJ documents from the 2000s describe how some communities even formed “Watchforce” units of citizens “who participate in surveillance and reporting of community problems” as part of their year-round follow-up to NNO. In this sense, NNO’s evolution has mirrored broader trends in community policing: encouraging civilians to be vigilant and work hand-in-hand with law enforcement, blurring the line between community cohesion and community surveillance.

National Night Out’s primary function is public relations, not crime prevention. NNO is a textbook example of copaganda: a feel-good spectacle that promotes police/community partnerships while glossing over deeper issues of police misconduct and systemic harm. As writer Netfa Freeman explains in Black Agenda Report, the event is designed to obscure the real role of police, which is to enforce racial capitalism, control the poor, and maintain the status quo. The block parties and smiling officers are a deliberate image makeover for an institution that, on the other 364 days of the year, continues to surveil, oppress, and inflict violence on those same communities.

This dynamic was on full display in Los Angeles in 2024, when Centro CSO staged a disruption of LAPD’s National Night Out event in Boyle Heights, calling it a propaganda event designed to wash the blood off the department’s hands. Protesters carried banners naming local victims of police killings and chanted “No peace without justice,” highlighting the contrast between the LAPD’s friendly “peace march” and its ongoing violence against Black and Brown residents. As Melina Abdullah of Black Lives Matter Los Angeles has explained, copaganda efforts like NNO are specifically designed to train the public to see police as heroes, downplaying patterns of abuse and state-sanctioned harm. Events like this serve to reset the narrative in favor of the police each year.

This dynamic was on full display in Los Angeles in 2024, when Centro CSO staged a disruption of LAPD’s National Night Out event in Boyle Heights, calling it a propaganda event designed to wash the blood off the department’s hands. Protesters carried banners naming local victims of police killings and chanted “No peace without justice,” highlighting the contrast between the LAPD’s friendly “peace march” and its ongoing violence against Black and Brown residents. As Melina Abdullah of Black Lives Matter Los Angeles has explained, copaganda efforts like NNO are specifically designed to train the public to see police as heroes, downplaying patterns of abuse and state-sanctioned harm. Events like this serve to reset the narrative in favor of the police each year.

National Night Out is also a strategic tool used to justify police budgets and power. As Alec Karakatsanis of Civil Rights Corps has documented, distorted portrayals of police in the media and in community events are used to secure larger budgets, resist oversight, and shore up political legitimacy. NNO is often held during summer budget season, when cities finalize spending plans. Police departments use these events to present themselves as community-focused institutions, leveraging public goodwill to block reform and argue for more money. In 2022, Jessica Pishko noted how that year’s NNO coincided with law enforcement agencies nationwide complaining about hiring shortages and using the event to rehabilitate their public image. These PR moments are explicitly designed to boost recruitment and retention by making policing look community-based and desirable. As Vox observed in its analysis of NNO, real safety requires addressing the inequalities and unaccountability that make police fundamentally untrustworthy in many communities.

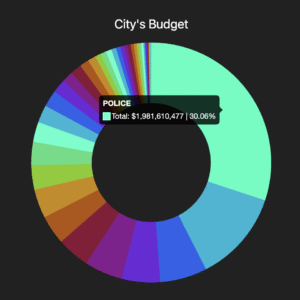

It’s no coincidence that the city can throw a well-funded photo-op for LAPD at Mar Vista Park while basic park maintenance and improvements go unfunded. As City Controller Kenneth Mejia has documented, LAPD receives the largest share of Los Angeles’s unrestricted general fund, consuming nearly half of the city’s discretionary spending, while departments like Recreation and Parks are left scraping for resources. This year, the city faced a $1 billion budget shortfall, yet the mayor and City Council continue to prioritize police spending over public services. In fact, Mar Vista Park—the very site of this year’s National Night Out—has increasingly relied on annual donations from nearby Windward School through a public-private partnership that gives the private school regular access to public fields and facilities. Windward has donated at least $25,000 per year since 2009 and previously contributed $150,000 for park upgrades, funding projects like tree planting and a new batting cage. These donations help keep the park running—but they also entrench a model where private wealth shapes public access. That kind of deal turns public space into a privilege, not a right, and reflects a broader pattern: LAPD gets hundreds of millions for surveillance and overtime while community infrastructure is quietly handed over to private institutions. If our parks are underfunded, it’s not because of some unavoidable scarcity—it’s because we’re prioritizing police over the public good.

It’s no coincidence that the city can throw a well-funded photo-op for LAPD at Mar Vista Park while basic park maintenance and improvements go unfunded. As City Controller Kenneth Mejia has documented, LAPD receives the largest share of Los Angeles’s unrestricted general fund, consuming nearly half of the city’s discretionary spending, while departments like Recreation and Parks are left scraping for resources. This year, the city faced a $1 billion budget shortfall, yet the mayor and City Council continue to prioritize police spending over public services. In fact, Mar Vista Park—the very site of this year’s National Night Out—has increasingly relied on annual donations from nearby Windward School through a public-private partnership that gives the private school regular access to public fields and facilities. Windward has donated at least $25,000 per year since 2009 and previously contributed $150,000 for park upgrades, funding projects like tree planting and a new batting cage. These donations help keep the park running—but they also entrench a model where private wealth shapes public access. That kind of deal turns public space into a privilege, not a right, and reflects a broader pattern: LAPD gets hundreds of millions for surveillance and overtime while community infrastructure is quietly handed over to private institutions. If our parks are underfunded, it’s not because of some unavoidable scarcity—it’s because we’re prioritizing police over the public good.

Mainstream media play a crucial role in promoting National Night Out. Local news outlets flood their channels with heartwarming images of cops grilling food, high-fiving kids, and smiling next to bouncy houses. That media spectacle is a central part of the event’s purpose. Police PR teams organize their own coverage and ensure these moments are widely circulated to shape public perception. Corporate media reinforce the narrative that police are friendly, essential protectors, and this erases the everyday violence of policing. Rarely do these stories mention the beatings, killings, and surveillance that define daily life for over-policed communities. The Stop LAPD Spying Coalition and Movement for Black Lives have called this out repeatedly, reminding the public that image is not reality, and that photo-ops cannot erase the blood on police hands.

National Night Out doesn’t just distract from harm—it facilitates it. The smiling officers at the BBQ may be the same ones working with ICE to detain your neighbors. Events like NNO are designed to build trust that allows for deeper surveillance and community control. In states like Florida, laws now offer bonuses to officers who collaborate with ICE, and across the country, LAPD and other departments continue to share license plate reader data and surveillance footage with federal immigration agencies. When police throw block parties in immigrant neighborhoods, they are not protecting the community—they are gathering intel and building cover for more policing. The presence of smiling officers at these events can make people let their guard down, leading them to volunteer information or support policies that will ultimately criminalize their own communities. Meanwhile, real community safety like housing, healthcare, childcare, eviction protection, goes unfunded and ignored.

Abolitionist organizers have begun pushing back. Since 2013, the Ella Baker Center has hosted “Night Out for Safety and Liberation” as a direct alternative to National Night Out. Instead of partnering with police, these events center community voices, mutual aid, healing justice, and survival. At Night Out for Safety and Liberation events, you’ll find tenants’ rights clinics, healing circles, poetry, and collective visioning—not militarized patrols or surveillance booths. Groups in New York and L.A. have also disrupted official NNO events, chanting the names of people killed by police and demanding that neighbors stop trusting PR stunts.

National Night Out is not a celebration. It is a distraction. It is a weaponized PR event that launders the reputation of violent institutions while they expand their budgets and evade scrutiny. Policing will never be made safe by a selfie or a hot dog. The work of real safety is done by neighbors who feed each other, care for each other, and protect each other from the violence of policing itself. If you see a National Night Out event happening in your neighborhood this year, don’t be fooled. Show up with the truth. Show up with a vision for something better.