Mayor Karen Bass is calling on LA City Council to grant a one-time exemption from Measure ULA for Pacific Palisades homeowners whose properties were damaged or destroyed in this year’s wildfires, a move that has drawn praise from residents recovering from disaster but criticism from housing advocates who say it undermines the city’s voter-approved “mansion tax.”

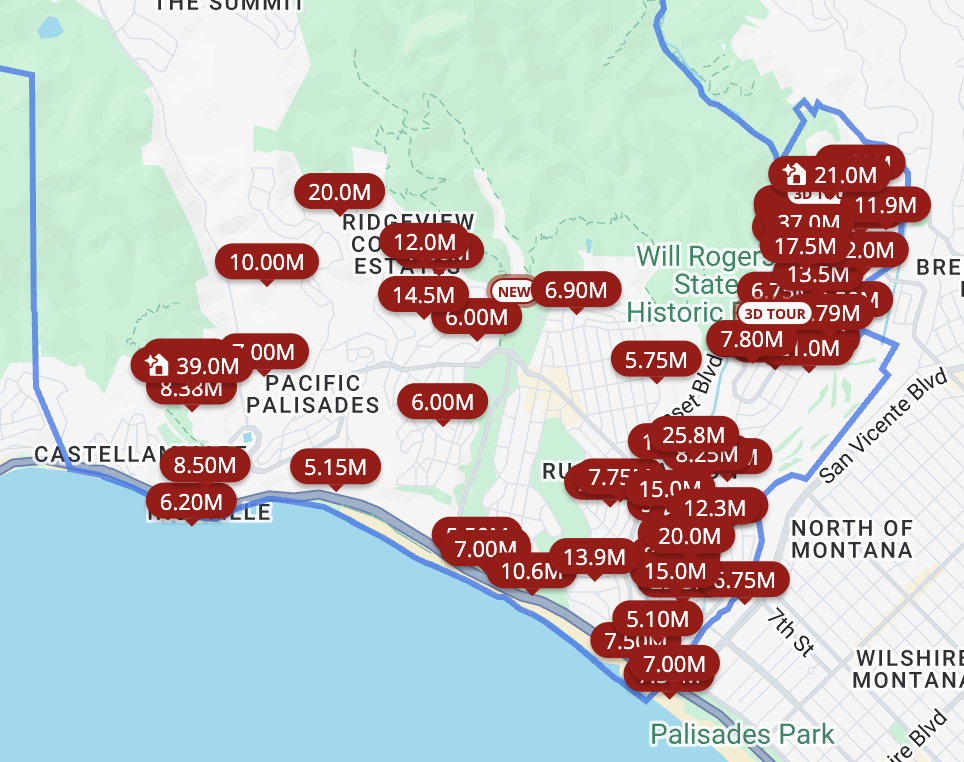

In a letter to City Council dated October 9, Bass proposed a three-year exemption for residents affected by the January fires. Measure ULA, approved by voters in 2022, created a real estate transfer tax on property sales above $5.3 million, with revenues dedicated to affordable housing and homelessness prevention. The mayor said the temporary relief would “help homeowners who need to or wish to move from the fire-impacted area and speed up sales of these properties and spur rebuilding and rehabilitation of the Palisades.”

During a September 17 webinar, Bass told residents, “I feel passionately that anyone who lost their home or was affected by the fires shouldn’t have to pay the transfer tax.” She argued that the measure, while essential for housing production, did not anticipate natural disasters, and that ULA’s costs were now depressing sale prices in fire-damaged neighborhoods.

Under Bass’s proposal, the City Council would first pass an ordinance giving the director of finance authority to create rules for the exemption. The mayor would then issue an executive directive instructing the department to enact it. Her office said the exemption would apply only to owner-occupied residential properties in the Palisades at the time of the fire, and that it would avoid loopholes while preserving long-term revenue since rebuilt homes would still pay ULA when sold again in the future.

On paper, the plan sounds straightforward. But housing advocates say it highlights how Los Angeles continues to tailor policy around affluent property owners rather than tenants. Measure ULA applies only to real estate sales over $5.3 million. Critics argue that anyone selling a $5 million home, even one damaged by fire, is not in financial distress.

“This is a tax on high-value assets, not hardship,” said one housing organizer. “If you’re selling a multimillion-dollar home, you don’t need a break from a program that keeps renters housed and builds affordable housing.”

The proposal followed a meeting between Bass and developer Rick Caruso, who has long opposed ULA and owns commercial property in the Palisades. Caruso praised the idea as common sense, saying it would help speed recovery. For housing advocates, that alignment raises concerns. A mayor who has touted ULA revenues as critical to financing LA’s housing goals now appears to be advancing a policy that echoes one of its fiercest critics.

Since taking effect in 2023, ULA has raised more than $830 million for affordable housing and homelessness prevention. The funds support eviction defense, rental assistance, and new affordable construction. Bass herself has credited the measure with helping stabilize thousands of households.

Supporters of ULA say carving out an exemption, even a narrow one, risks undermining the program’s credibility and consistency. Housing advocates warn that once the city starts making exceptions to a voter-approved measure, more will follow. After all, if Los Angeles makes room for one wealthy neighborhood, others will likely demand the same treatment.

The broader debate extends beyond Palisades fire recovery. A recent Jacobin article argued that disasters like the Palisades fire reveal the limits of Los Angeles’s market-based approach to rebuilding. After Singapore’s 1961 Bukit Ho Swee fire, the city-state responded by constructing public housing at scale, rehousing thousands within months and laying the foundation for one of the world’s most successful social housing systems.

By contrast, Los Angeles continues to rely on private development, tax incentives, and one-off exemptions rather than public investment. The city owns vacant lots, has a public housing authority, and now possesses a dedicated revenue stream through ULA, yet much of that capacity remains underused and leadership’s knee-jerk reaction is to weaken the revenue stream.

Bass argues that the exemption could ultimately strengthen ULA by accelerating rebuilding and future taxable sales. But housing economists and advocates say what slows progress most is not taxation but uncertainty. Each time the measure is reopened to legal or political challenge, it introduces new doubt into the system. “Stability builds housing,” one advocate said. “Uncertainty delays it.”