On Tuesday night, residents packed the Mar Vista Recreation Center for a community meeting that, on its face, concerned a modest update to a youth sports facility. In reality, it became a familiar Westside argument about who gets to use public space and who feels entitled to constrain it.

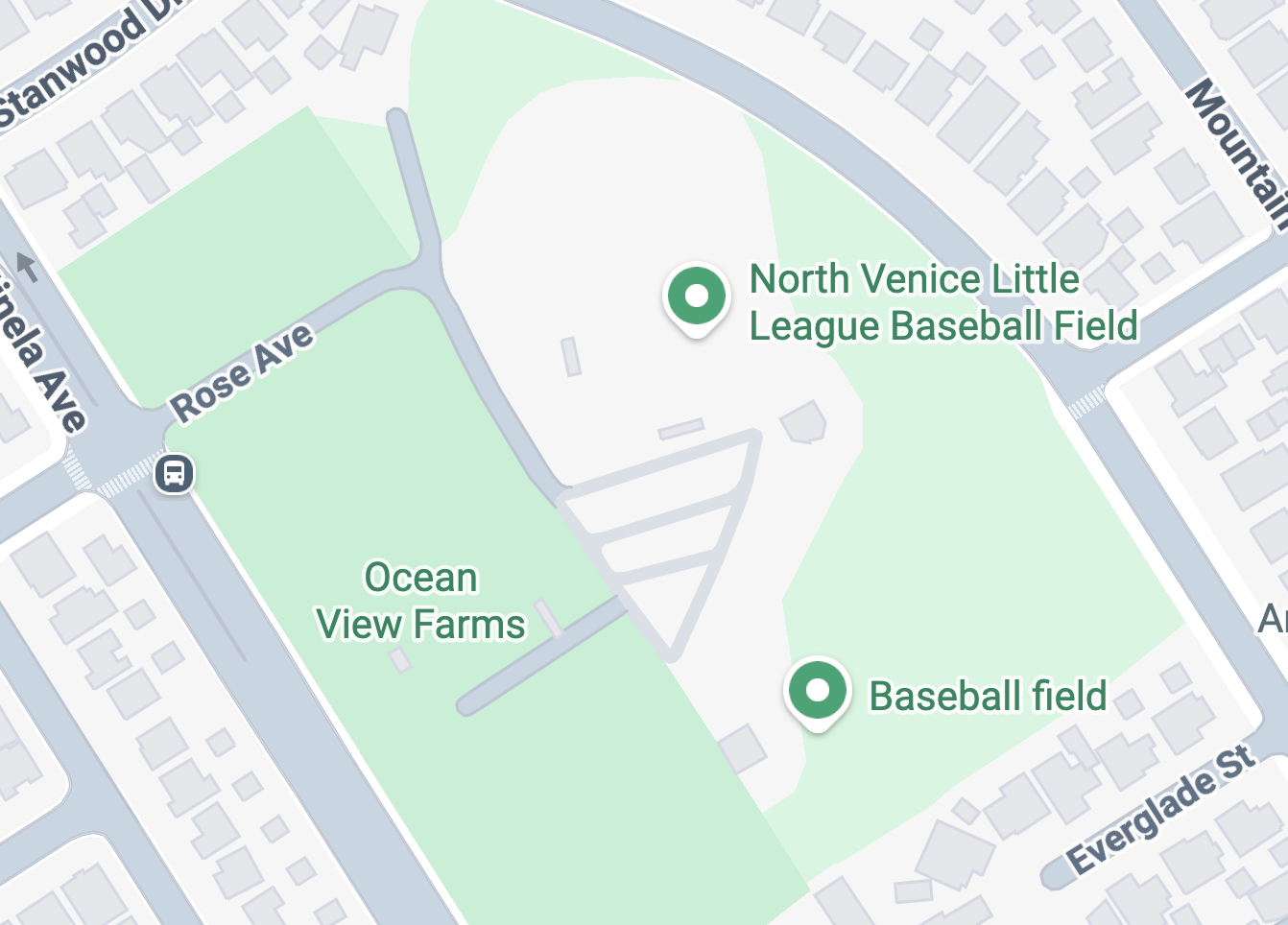

The meeting was convened by the council office and the Los Angeles Department of Recreation and Parks to hear feedback on a proposal from North Venice Little League to add a small T-Ball field within the league’s existing footprint near Grand View. The field would primarily serve children ages four to seven and allow younger baseball and softball players to practice at their home fields rather than being sent to parks farther away.

The room leaned strongly in favor of the proposal, with one attendee describing the split as roughly 80–20 supporting the league. That was not immediately obvious. When public comment began, nearby homeowners who had signed up in advance spoke first, several in a row, briefly creating the impression that opposition dominated the room.

Those raising concerns were homeowners who live along the southeast edge of the Little League property, an area organized by Hilltop Neighbors Association. The association’s own framing helps explain the tone of the opposition. Its stated focus on “crime prevention,” “emergency preparedness,” and residents’ “quality of life” reflects a worldview that tends to treat increased public use not as community vitality but as a risk to be managed. Many speakers began by affirming their support for youth sports before pivoting to objections about parking, noise, privacy, and inconvenience. Some worried about balls landing in their yards, despite the fact that the proposed field would be oriented away from nearby homes and used by very young children.

The tone was mostly friendly, but the substance of the concerns was revealing. Comments focused on possibilities like “there just might be less parking on my street for certain hours” or hearing more kids playing nearby. Many of the homeowners speaking have older children who have already aged out of the league, and the subtext was hard to miss. The space was embraced when their families needed it, but contested now that others do.

Neighbors have long resisted broader public access to the site, pressure that keeps the gate on the Grand View side of this “public” park locked. In a neighborhood with few open green spaces where people can walk, sit, play, or rest, that restriction does not square with the park’s purpose. By comparison, it is hard to imagine Mar Vista Recreation Center locking its fields or playground during the day to accommodate nearby homeowners, yet that is effectively what is happening here. Living next to a public park means accepting that people will use it and come and go as part of everyday life.

What went largely unspoken at the meeting was the deeper history of the site itself. The Little League fields sit on Mar Vista Hill, land that has never been residential. After Mar Vista was annexed into Los Angeles in the 1920s, the hilltop was acquired for municipal use, including a planned water reservoir that was never built. During World War II, it was actively used for military installations. When the war ended and surrounding farmland was rapidly developed into housing, the hill was deliberately preserved for public and recreational uses.

That context matters. The needs raised by families in support of the field align closely with how this land has long been intended to function as active, shared community space.

As more supporters spoke at the meeting, the conversation widened to how the site is actually used today. Parents and coaches described a league serving hundreds of kids each year, with younger teams often pushed to practice at other parks because older divisions receive priority for limited field time. Those other fields are farther away and not maintained to the same standard as the North Venice complex, making practices less accessible and less consistent for younger players.

Notably, the proposal does not expand the league’s footprint. The new field would be built entirely on land already designated for Little League use, activating an underused patch of grass and dirt between existing diamonds and a fence. Supporters pointed out that as an actively used field, the area would be regularly maintained rather than left idle.

The meeting remained mostly civil, but it was instructive. “If you are even willing to come out in opposition to something that is so noncontroversial,” one attendee reflected afterward, “I can only imagine how emboldened people feel when the opposition is a vulnerable community.” She noted that the proponents of the field were themselves largely upper-middle-class white parents asking for something as innocuous as a place for their kids to play T-Ball. If neighbors are willing to organize against a privileged group over a request this modest, she observed, it helps explain how much harsher and more aggressive that opposition can become when the people seeking public space are renters, low-income residents, unhoused people, or people of color.

A representative from Councilmember Traci Park’s office attended the meeting but did not take a position, noting that Recreation and Parks will make the final determination after reviewing community feedback. The proposal is expected to move next to an environmental review and additional approvals.