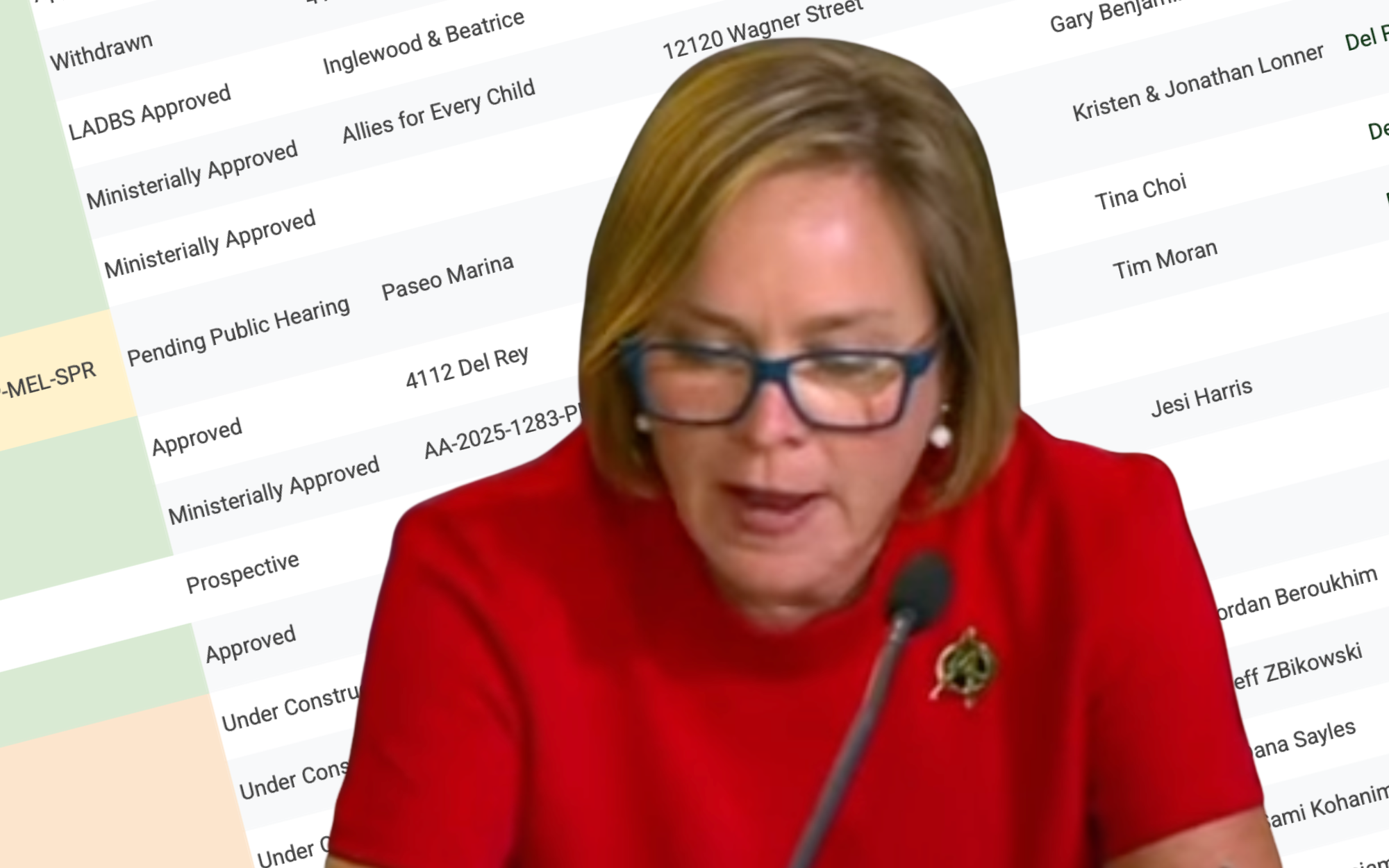

Councilmember Traci Park’s claims about a massive surge in housing production in Council District 11 are not supported by the city’s own records. After Park told constituents that 65 projects totaling 5,800 units had “advanced” during her tenure, with 30 more projects in the pipeline putting the district “on track to deliver 9,300 units,” the CD11 Coalition for Human Rights filed a California Public Records Act request requested the data behind these numbers. Park’s office produced the internal spreadsheet she relied on, and a detailed review shows that the numbers in her newsletter do not reflect the reality of housing development in the district. The data reveals older filings, stalled projects, withdrawn proposals, and ministerial approvals that do not involve council authority. It also confirms that very little of the district’s housing production began under Park or is moving because of her leadership.

The dataset shows that most units in the CD11 pipeline originate from TOC incentives, density bonus filings, ED1 fast-track approvals, and a handful of SB 35 streamlining cases. These are state or city programs that limit discretionary review. They advance whether a councilmember supports them or not. In fact, many of the units currently moving forward in CD11 exist because of TOC and ED1, both of which Park has criticized and neither of which she initiated. The data confirms that the production happening in the district is driven by long standing planning rules and state law rather than council intervention. Nothing in the spreadsheet shows a new surge of activity attributable to Park.

Many of the projects counted in Park’s public claims predate her election. Some filings go back six to eight years. Numerous TOC projects in Sawtelle, Venice, and West LA were initiated between 2017 and 2021. A number of projects remain in planning review years after filing, showing no significant movement during Park’s tenure. Others listed in the spreadsheet have been withdrawn or abandoned entirely. A few appear multiple times under different case numbers, which would inflate totals if someone simply added up the rows without understanding the distinctions.

Affordable units in the dataset follow the same pattern. There is a modest number of affordable units generated through TOC and density bonus requirements. These units are required by law in exchange for development incentives. They are not created by council directives. ED1 has produced a small number of ministerially approved affordable projects as well, but their movement is administrative. Park does not control those approvals. The dataset includes no evidence of new deeply affordable housing initiatives originating from her office.

The data also shows how rare projects like Venice Dell are. Among the hundreds of filings in the tracker, very few are 100 percent affordable. Even fewer are sited on public land. Venice Dell is one of the only deeply affordable, shovel-ready projects in a high resource coastal neighborhood. Its long delays stand out precisely because everything else in the data consists of private development filings where affordability is limited and often minimal.

The CPRA records also highlight the structural issues created when political claims are not grounded in real project data. When withdrawn or stalled filings are treated as active housing production, it creates a misleading picture of district-level progress. When older TOC or ED1 projects are credited to a councilmember who had no role in initiating them, it obscures the actual forces driving new housing. When duplicate listings inflate totals, it becomes even easier to misrepresent the pipeline.

The statewide scrutiny around Venice Dell underscores the risks of this approach. Four days before Park published her housing claims, the California Department of Housing and Community Development issued a formal Letter of Inquiry warning Los Angeles that it may be violating state housing law by delaying the fully approved project. Venice Dell has City Council approval, Coastal Commission approval, and secured state funding, yet has been held up by political intervention. The CPRA housing data shows how unusual it is for a district to have a deeply affordable project of this scale. Blocking such a project sends a signal that even when developers follow every rule, meet every requirement, and survive every hearing, a council office can still derail it.

The implications reach beyond Venice. If councilmembers can selectively delay or obstruct fully approved affordable housing while taking credit for units produced by state or mayoral mandates, it weakens public understanding of where housing actually comes from and undermines efforts to meet state production requirements. It also threatens to discourage affordable housing developers who rely on predictable, lawful processes.