When a video of Catie Laffoon refusing to start her public comment at LA City Council until every councilmember looked up from their phones went viral, it wasn’t just because of her message. It was the urgency in her voice and her refusal to accept the silence that so often greets community members in crisis.

Laffoon isn’t a politician or a professional advocate. She’s a photographer and activist who has become one of the most visible witnesses to Los Angeles’ escalating immigration raids and the police violence that often accompanies them. Her footage from a downtown protest showing LAPD corralling demonstrators, blocking every exit, then unleashing rubber bullets, batons, and pepper balls spread widely online even as major outlets refused to run it.

Mar Vista Voice: You’ve been in the streets, you’ve been at City Hall. Can you tell me how that journey began for you?

Laffoon: I’ve always been an activist. I’ve always felt really passionately about injustice, even when I was little, like a five-year-old on a soapbox. I began showing up at protests with my stills camera because I thought it was important to be a witness to history and to the truth. On June 8, I remember standing in my apartment getting dressed and stopping myself. Normally I would wear all black, like I always do. But I had this gut feeling. I put on blue jeans and I wore my hair down. Something felt off before I even left the house.

I told myself I wouldn’t wear a press badge that day because the press can’t intervene. They’re supposed to be neutral, and I already knew that if things went sideways, I couldn’t just stand there. It’s why I wore my hair down. I knew if something bad happened my whiteness might be able to shield people. And sure enough, about twenty minutes in, I realized this protest wasn’t like anything I’d ever seen in America. It felt like something I’d watched play out a hundred times in a movie.

We were supposed to march a loop from City Hall, through Little Tokyo, and back. But LAPD stopped us right at Temple and Garey St., forcing us toward Alameda, straight up the block with the freeway on one side and the detention center on the other. And they set up their line at the far end of the street instead of the beginning. If they didn’t want us near the detention center, their line would have been at Temple and Alameda. That’s when I realized they wanted us bottlenecked. It felt like a trap, like something out of The Hunger Games. They were orchestrating a situation for the photo op. It all felt deliberate, like they wanted to create a situation to get the protesters to react.

We stopped, I don’t know, maybe 20 feet from their line. They waited for the street to pack and then they charged at us. They got very aggressive with the front line, who weren’t doing anything but chanting; they were not violent or throwing anything.

At that point, I put my stills camera away. I didn’t know how to tell this story through stills. If you go to my Instagram and scroll down, you can actually see where the videos begin. Before that it was all work—never photos of me, not much personal, just celebrity photography. The third video in the series is the one where I began filming the police. It’s about twenty minutes, one continuous shot. What I caught in those minutes still makes my stomach drop. The police charged a man so hard they knocked him out of his prosthetic legs. He hit the ground, helpless, and he tried to crawl away from them. Officers swarmed him. He had nothing on him, he wasn’t dangerous, but they beat him with batons anyway. You can see me and others trying to plead with them: let us help him, just let us help him. They gave us about half a minute before turning their weapons on the crowd. They beat us for trying to help him. Then they dragged him behind their line, out of our sight. From where I was, I could see what looked like them kneeling on his neck and back, pinning him down like George Floyd—only this man had no legs, no leverage to resist.

At that point, I put my stills camera away. I didn’t know how to tell this story through stills. If you go to my Instagram and scroll down, you can actually see where the videos begin. Before that it was all work—never photos of me, not much personal, just celebrity photography. The third video in the series is the one where I began filming the police. It’s about twenty minutes, one continuous shot. What I caught in those minutes still makes my stomach drop. The police charged a man so hard they knocked him out of his prosthetic legs. He hit the ground, helpless, and he tried to crawl away from them. Officers swarmed him. He had nothing on him, he wasn’t dangerous, but they beat him with batons anyway. You can see me and others trying to plead with them: let us help him, just let us help him. They gave us about half a minute before turning their weapons on the crowd. They beat us for trying to help him. Then they dragged him behind their line, out of our sight. From where I was, I could see what looked like them kneeling on his neck and back, pinning him down like George Floyd—only this man had no legs, no leverage to resist.

That was the moment when I realized this wasn’t just about creating images of “violent protesters.” They were willing to kill people.

And it kept escalating. At one point, I kept trying to shield two young women who had been targeted again and again by an officer. One of them was maybe 21, and the officer repeatedly swung his baton at her head and into her stomach, so I began putting myself between her and his baton. He’d stop when it was me.

Eventually we all got pushed back far enough that we thought we were safe. People started to let down their guard, wipe their faces, flush their eyes. I even turned my camera off for a moment. Then, out of nowhere, the police charged like linebackers, full speed into the line. The girl went face down on the pavement and they swarmed her, beating her. The girlfriend threw herself on top of her. I dove in too, but the same officer grabbed me by the neck and threw me back, never breaking eye contact.

I tried to tell him I wasn’t a threat—I just wanted to help. “I’m peaceful! I’m not a threat! Please let me help her!” He raised his baton and closed the 8–10 feet of space between us and swung for my head with everything he had. I ducked, shielded myself with my hand, and fell to the ground hard. I realized I couldn’t use my hand anymore. I thought it was broken. I began to move toward the girls when I felt several arms grab me from behind and drag me back to safety behind our line. I could see the girls still being beaten—four officers swinging down over and over—and then they were dragged behind the line. I never saw them again. I don’t believe they were okay after that.

I was useless without my hand; I had to leave. I went to urgent care, but first I pushed my footage out to friends in nonprofits and media. I told them this wasn’t like anything we’d seen before in America. This was different. This was police staging violence for the cameras, creating the narrative that protests were chaotic and violent when the opposite was true. I said, send out the Bat-Signal. Share this. If I’m wrong, don’t use it. But if I’m right, the world needs to see it.

And here’s the part that broke me. Nobody ran it. CNN didn’t air it, possibly because it wasn’t exclusive. Al Jazeera and MSNBC didn’t either. I even had personal contacts, direct emails, and it was silence. Shut down. Not interested. And I realized then how deep the suppression went. There was a storyline being sold on both sides, and my footage showing the truth didn’t fit. I was very clear to everyone that the story of violent protesters, of rioting, of chaos—it was manufactured. The violence was coming from one side—it was coming from law enforcement and the government—and it was intentional. I showed them. We have shown everyone. And nobody would run our footage or touch the idea that the violence was coming from the authorities and not the people.

Before that, I still thought maybe the system could work if we just told the truth loudly enough. After that, I knew the truth could be buried. And that terrified me more than anything that happened in the street.

Mar Vista Voice: You’ve talked about how what you saw on the ground sort of set off a chain reaction that eventually led you into City Hall. Can you walk me through that connection?

Laffoon: I was out there every day, protesting, watching what was happening, and meanwhile all the politicians in our city—in particular the mayor—were saying one thing to the public and the media, but the policies in place on the ground contradicted everything they were saying. It was dangerous. People were getting hurt, and I knew people were going to die if nothing changed. That’s what pushed me toward City Hall. Because I kept thinking: if we have elected leaders, and given the level of crisis, if they’re not talking about it every single day, something is very wrong. That was just my gut, and I wasn’t seeing that at all.

Mar Vista Voice: When you stood up in City Hall and refused to speak until they paid attention, was that planned? Or did it happen in the moment?

Laffoon: Truly, it just happened. We had first shown up on Wednesday, the first council meeting after their summer break. And protesters had begged them not to even take that break. How do you go on recess in the middle of a state of emergency? So Wednesday comes, we pack the gallery. Protesters who had been on the ground, people terrified about what’s happening with LAPD and ICE…

And on the agenda that day were items that spoke directly to the crisis: immigration enforcement, LAPD response, emergency response, all of it. But when it came time for public comment, they only allowed thirty minutes, which meant about seven people. Every city council has their regulars who are there just to disrupt and sing jingles and more or less be assholes. The first five were those people. Only two protesters got called. And while those two people spoke, begging for help, telling them what’s happening in the streets, the council didn’t even look up. Not once. They never made eye contact, never acknowledged the fear and urgency in the room. Then they closed public comment. We knew they had the option to extend it—they just chose not to. So the gallery started chanting: Please let us speak. Please let us speak.

But instead they just moved on. And that’s when I stood up. I was like, Come on, you’ve had all summer. Please give us twenty minutes. Everyone’s scared. But the council president just kept shutting me down. He wouldn’t listen. He only ever looked up to reprimand me.

Mar Vista Voice: And then they moved to remove you?

Laffoon: Yeah. When they started calling the cops over, I stepped out of the pew because I was sitting with other protesters who weren’t white, and I wanted the attention on me, not them. But I immediately noticed that while I was the one speaking, they were circling around the only Black woman in the gallery. She was literally just sitting there working on her laptop. Calm as could be. Not chanting, not yelling. And I clocked it right away: I actually said it out loud—why are you talking to her, I’m the one causing a ruckus!

Eventually, they agreed that if I left, everyone else could stay. So I did. And I thought that was the end of it. But no—as soon as I was gone, they removed another protester and then arrested the Black woman, arrested her for trespassing. That’s what we were walking into when Friday rolled around.

Mar Vista Voice: And Friday is the day of the viral video.

Laffoon: Exactly. By Friday, I had a whole list of demands on my phone: hold town halls in every district, explain what their plan was to keep families safe so kids could return to schools, stop LAPD from acting as ICE’s bodyguards, address the fear in our communities. All of it.

But again, they weren’t listening. Speaker after speaker went up, and no one on the dais looked up. Not once. And the agenda items that day were about, I don’t know, speed bumps or something. Nothing tied to the actual crisis. Which meant we were only allowed sixty seconds of general comment. So I thought, okay, if I only have a minute, then I’m going to make damn sure they hear me.

And you’ve seen what happened. They didn’t pay attention. The council president even rolled his eyes, laughed, told me to wrap it up while I was pleading for them to listen. And something in me just snapped. Normally I’d try to contain myself—you know, be appropriate, be polite, because that’s what women are taught to do. But I couldn’t. Not after everything I’d seen. Not after watching people beaten and arrested on federal charges for nothing.

So I let it all out. The anger, the grief, the urgency. I just couldn’t play by their rules of “decorum” anymore. Not when lives were on the line.

Mar Vista Voice: You’ve brought up your own privilege as a white woman in the context of these protests and your presence at City Hall. Can you expand on that? How do you think about the way being a white woman shapes how people respond when you put yourself on the front lines, especially given how we’ve seen videos of white women confronting ICE agents or police go viral in ways that don’t happen when others take the same risks?

Mar Vista Voice: You’ve brought up your own privilege as a white woman in the context of these protests and your presence at City Hall. Can you expand on that? How do you think about the way being a white woman shapes how people respond when you put yourself on the front lines, especially given how we’ve seen videos of white women confronting ICE agents or police go viral in ways that don’t happen when others take the same risks?

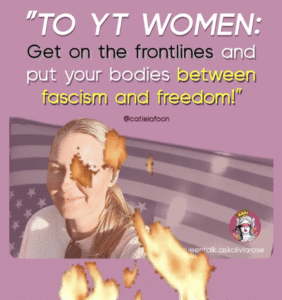

Laffoon: This is something I’ve been saying from day one. White women have never had more power than they do right now, in this moment. It’s a very short window, but it’s real. We have this chance to literally help save thousands of people, to stand between them and harm, to save democracy, to finally stand up and step into that power and use our privilege in a heroic way. And the question is, what are you going to do with that power?

Because if you don’t use it now, you won’t have it later. Power doesn’t last forever. I think about how women around powerful men are treated, and it’s clear: the only women who stay close to power are the ones who elevate wealthy men. Victims don’t get that. Survivors don’t get that. Only the women who play along. But that proximity only lasts as long as the men allow it.

So right now, in this moment, I look at white women and think: you actually have leverage. And what are you going to do with it? Are you going to spend it protecting the status quo, or are you going to spend it protecting people who are being targeted? Are you going to use that leverage to get out from under the thumb of men?

Honestly, sometimes I just wish I could grab every Lululemon-wearing white woman I see and say: Put on your yoga pants and go out there. Use that privilege. Stand in front of ICE. Stand in front of LAPD. Use the fact that people look at you differently and pay attention to you differently. Because that’s really all I wanted to do from the beginning: motivate white women to step out of their comfort zone and use the power they have while we have it.

Mar Vista Voice: You’ve said before that “the fight is with ICE” and you even urged LAPD to be on the community’s side. I want to ask you to expand on that. For many, the critique has been that police are complicit with ICE, not a counterweight to them. Most people who go to City Hall to testify against police brutality are saying “abolish the police,” not “stand with us against ICE.” So when you framed it the way you did, it landed differently. Do you believe that kind of alliance is possible? Or was it more about forcing City Hall to pay attention? And if it were possible, what would it look like in practice?

Laffoon: It definitely wasn’t about grabbing attention. Honestly, right now my brain just boils everything down to its simplest parts. LAPD’s job—at least on paper—is to protect the people of Los Angeles. That’s their job. And I don’t love them, I’m terrified of them, but technically that’s what they’re supposed to do. So why aren’t they doing it?

Other cities around here have drawn lines. Huntington Park, for example, has said flat-out they’re not working with ICE. Their police chief instructed local law enforcement to protect residents, not federal agents. So did Seattle. So if those places can do it, why can’t Los Angeles? We’re one of the biggest cities in the country. Are you telling me that one of the most militarized police departments in the country can’t stand up to ICE? That doesn’t make sense.

Mar Vista Voice: And yet city officials don’t seem to be demanding that.

Laffoon: Exactly. Even if LAPD isn’t inclined to take that stance themselves, why aren’t city leaders demanding it of them? To me, being on the ground feels like war. And in a war, if guns are pointed, I’d rather LAPD point theirs at ICE than at us. That’s the reality. Do I love them? No. But would I rather they be on our side? Of course. We can get back to our differences later. Right now the crisis is too urgent. Everyone standing up to ICE comes from a different background, but we all agree this is historically, world-ending bad. To do nothing would be worse.

And that’s where the hypocrisy of city leaders comes in. For example, Mayor Bass tells the public that LAPD doesn’t work with ICE, and she urges people to stand up, fight back, record what’s happening, protect our neighbors. But when we actually do that, what happens? We are sitting ducks because local authorities are not out there making sure we are safe while doing those things. They actually punish us for doing them. The feds treat filming as “doxxing,” which is harassment of a federal agent. And assault is now simply an interaction where law enforcement shoves you, hits you, pushes you—they initiate violent contact with you, but you physically come into contact, so it’s assault. You could face 20 years in prison. We’re up against LAPD and the Sheriff’s Department on top of that. They’re not saying, “We’ve got your back.” They’re hurting and arresting us for doing the thing our mayor asked us to do.

That contradiction is so dangerous. It’s enraging. The city is basically sending people out into the streets with no protection, telling us to fight ICE, and then letting LAPD and federal agents brutalize and prosecute us for it. That’s what we’re up against right now.

That contradiction is so dangerous. It’s enraging. The city is basically sending people out into the streets with no protection, telling us to fight ICE, and then letting LAPD and federal agents brutalize and prosecute us for it. That’s what we’re up against right now.

Mar Vista Voice: On the Westside, our councilmember Traci Park has opposed sanctuary city protections, aligned herself with LAPD and Trump supporters, and consistently sided against tenants and workers. She has said almost nothing about these raids while the very communities most at risk remain in hiding. From your perspective on the front lines, what should we do about elected officials like her who aren’t just silent but actively causing harm?

Laffoon: I think we’re in a really interesting and difficult moment right now. A lot of us are mad because we’re realizing the system we’ve been living under—the one we’ve maybe held out a little bit of hope for—just doesn’t work. Even the glimmers of progress we thought we had—it’s clear those don’t hold. Coming to terms with that is like grief. You realize it doesn’t work, and then you have to ask: how do you make it work? I don’t have the answer. I’m vastly underqualified to solve that.

But I will say this: people are ready for change. There’s real power right now to push for it. If we want our city to look a certain way, I don’t think the solution is to keep looking toward traditional politicians. Anyone who wants that job for the sake of power—I don’t trust their motives. What we need are community organizers and on-the-ground leaders who are already doing the work, people who step up reluctantly but willingly because the community wants them to and they feel called to, not because they’re chasing a title.

And specifically in this case, I do believe there is power to unseat Traci Park. One thousand percent. If there’s a candidate who the community believes in, who is genuinely rooted in the fight for your neighborhoods, that seat is winnable. All of these councilmembers, honestly, are vulnerable because of how bad things have gotten. But it depends on whether people decide to organize, to believe in that possibility, and to push someone forward who actually represents them.