In Los Angeles, public schools are supposed to be the great equalizer. Yet within a few square miles of Mar Vista, the disparities among elementary schools tell a very different story. Parent fundraising, housing patterns, and historic segregation combine to shape a system where some schools flourish while others scrape by, despite existing within the same district and often just a few blocks apart.

At the center of this divide is Mar Vista Elementary. With strong test scores and a booster club that raises more than $1,000 per child annually, Mar Vista has become one of LAUSD’s coveted campuses. The school’s demographics reflect its affluence: only about 10 percent of students qualify as low-income, and roughly 60 percent are white. In a district that is more than 70 percent Latino and overwhelmingly low-income, Mar Vista stands out as a pocket of privilege. Housing prices within its attendance zone are among the highest in the area, effectively gatekeeping access to the school through property wealth.

Just a short drive away, Grand View Boulevard Elementary looks very different. Once serving more than 1,000 students, its enrollment has dwindled as more affluent families cluster in Mar Vista Elementary’s zone. Today, about 70 percent of Grand View students are low-income, and the student body is about 70 percent Latino. Parent fundraising here amounts to just $59 per student per year, not enough to cover the extra programs and staff positions that schools like Mar Vista can provide through parent contributions. Grand View’s attendance zone includes Mar Vista Gardens, the largest public housing complex on the Westside, along with blocks of rent-stabilized apartments along Venice Boulevard. Families in those units are among the most vulnerable in the city, facing housing instability and economic hardship, yet their children attend a school with only a fraction of the resources available just a few blocks north.

Beethoven Street Elementary falls somewhere in between. Drawing from parts of Mar Vista and Del Rey, it serves a student population that is more than half low-income and about 57 percent Latino. Parents here raise around $479 per student and can therefore provide enrichment like teaching assistants, art supplies, after-school programs. Beethoven’s catchment area includes a mix of single-family homes and apartment complexes, creating a socioeconomic blend that is reflected in its enrollment.

Walgrove Avenue Elementary sits east of Lincoln Boulevard in Venice. The school is racially mixed, with about a third of students qualifying as low-income. Parents raise around $742 per student, placing Walgrove in the middle tier of fundraising power among Westside schools. Its attendance zone includes neighborhoods that have seen an influx of newer, wealthier families. Across LAUSD, gentrifying schools have often seen fundraising groups and decision-making dominated by newer, more affluent parents, changing priorities and programming in ways that can leave longtime residents feeling sidelined.

Richland Avenue Elementary, located between the Expo/Bundy and Expo/Sepulveda stations, tells yet another version of the story. Its zone includes a heavier share of multifamily housing compared to Mar Vista Elementary’s single-family tracts. About 40 percent of students are low-income, half are Latino, and roughly a third are white. Parent fundraising averages $413 per student—a significant figure compared to Grand View, but less than half of Walgrove’s and far below Mar Vista’s. Richland demonstrates how even moderate differences in neighborhood wealth and housing composition can cascade into starkly different educational resources.

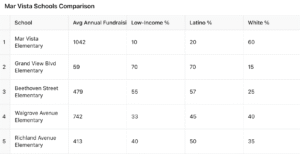

The disparities become clear in the numbers:

(This chart compares the five Mar Vista-area schools by average annual parent fundraising per student and their demographic breakdowns.)

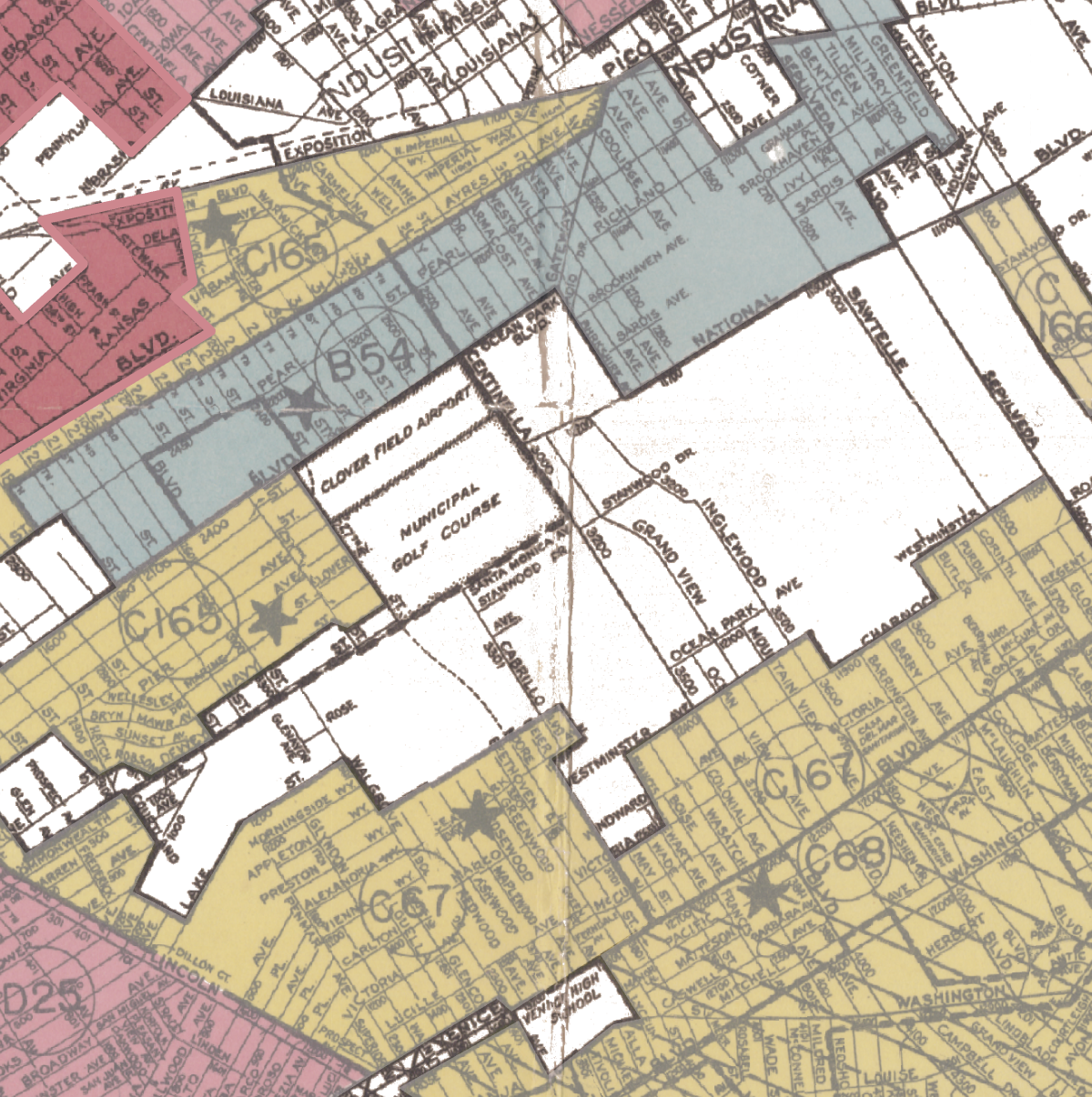

These contrasts cannot be understood without examining LA’s broader history. School attendance zones often mirror old patterns of housing segregation, particularly the redlining maps of the 1930s. In West Los Angeles, areas deemed “desirable” by the federal Home Owners’ Loan Corporation were reserved for white, middle-class homeowners, while neighborhoods with higher concentrations of Black, Latino, or immigrant families were marked “hazardous” for investment. Decades later, those lines still shape where families can afford to live, and, by extension, which schools their children attend.

The passage of Proposition 13 in 1978 further entrenched these inequalities. By capping property taxes, Prop 13 gutted California’s once top-tier school funding system. Before its passage, local property wealth directly translated into local school budgets. Afterward, Sacramento centralized funding, redistributing some money to poorer districts but dramatically lowering overall revenue. For wealthier families who wanted to maintain high-quality public schools, the workaround became parent fundraising. PTAs and booster clubs exploded in number in the 1980s and 1990s, effectively reintroducing inequality through private donations rather than property taxes. Parents at schools like Mar Vista Elementary can write $1,000 checks and raise hundreds of thousands each year, while families at Grand View struggling with rent or job insecurity, cannot.

The inequity is compounded by LAUSD’s open enrollment policies. On paper, open enrollment is supposed to offer students access to schools beyond their neighborhood zones, especially where declining enrollment has left empty seats. In practice, affluent schools with strong reputations rarely participate in meaningful ways. A recent analysis of district data showed that 24 of LAUSD’s most elite elementary schools had room for at least 4,306 additional students based on historical enrollment, yet they reported only 58 open enrollment seats among them. Even those 58 were concentrated in just four schools, which collectively had space for 466 students, meaning they offered access to only about 12 percent of their available seats. District-wide, the picture was just as stark: LAUSD’s elementary schools had over 214,000 empty desks in 2024, but only 3,000 were listed for open enrollment transfers, or about 1 percent. More than 300 elementary schools reported zero open seats, despite having 140,000 vacant spots among them. For years, principals were told that participation was “not mandatory,” effectively treating open enrollment as optional. It is only in the past couple of years that the district has begun pushing schools to comply with state law, but the culture of exclusion remains strong.

This dynamic protects schools like Mar Vista Elementary from broader access. Families who can afford the real estate premium or navigate the district’s internal permitting systems get in, while those without the means are left with fewer options. It creates a paradox, wherein even as LAUSD struggles with declining enrollment overall, with entire campuses closing or merging, some of its most well-resourced schools keep their doors largely closed to outsiders.

The case of Mar Vista’s elementary schools shows that LAUSD’s segregation is not simply the product of history, but of ongoing choices. District leaders approve expansions at already successful schools while nearby campuses sit half-empty. Attendance zones reinforce property values. Parents fill budget holes with private donations, but only in places where wealth is concentrated. The result is that the best public schools in Los Angeles are not truly public at all. They are preserved for those who can buy their way in, whether through mortgages or fundraising, while the promise of equal access remains out of reach.