On Friday, LA City Council approved new funding for LAPD after the department hired far beyond what the Council itself had authorized in the budget. The vote was framed as urgent and unavoidable, but by the time it reached the Council floor, the decision had already been boxed in. Mayor Karen Bass effectively gave LAPD the green light to expand hiring off-budget months earlier, publicly celebrating increased staffing while leaving City Council to sort out the financial consequences later.

That context matters, because Item 40 was never a clean question of whether LAPD should receive more money. That choice had already been made at the executive level. What Council faced instead was a bind created upstream: retroactively approve off-budget hiring or risk being blamed for stalled staffing and vague threats to public safety. As Councilmember Marqueece Harris-Dawson put it bluntly during the debate, “This council, given a majority, will fund the police department . . . so we should just expect that.” The remaining discussion was not about whether LAPD would be funded, but how City Council would formalize that outcome.

The procedural chaos that followed only deepened that democratic breakdown. Item 40 was pulled from the agenda by Councilmember John Lee, who acknowledged that “an amendment is being circulated” as the item came up for consideration. Councilmember Adrin Nazarian then moved to bifurcate Item 40, forcing the LAPD funding question to be taken up as a stand-alone vote instead of rolling through with the rest of the Budget and Finance Committee report. The bifurcation passed, opening the door to a cascade of amendments and substitutions that made it increasingly difficult to track what was actually being decided in real time.

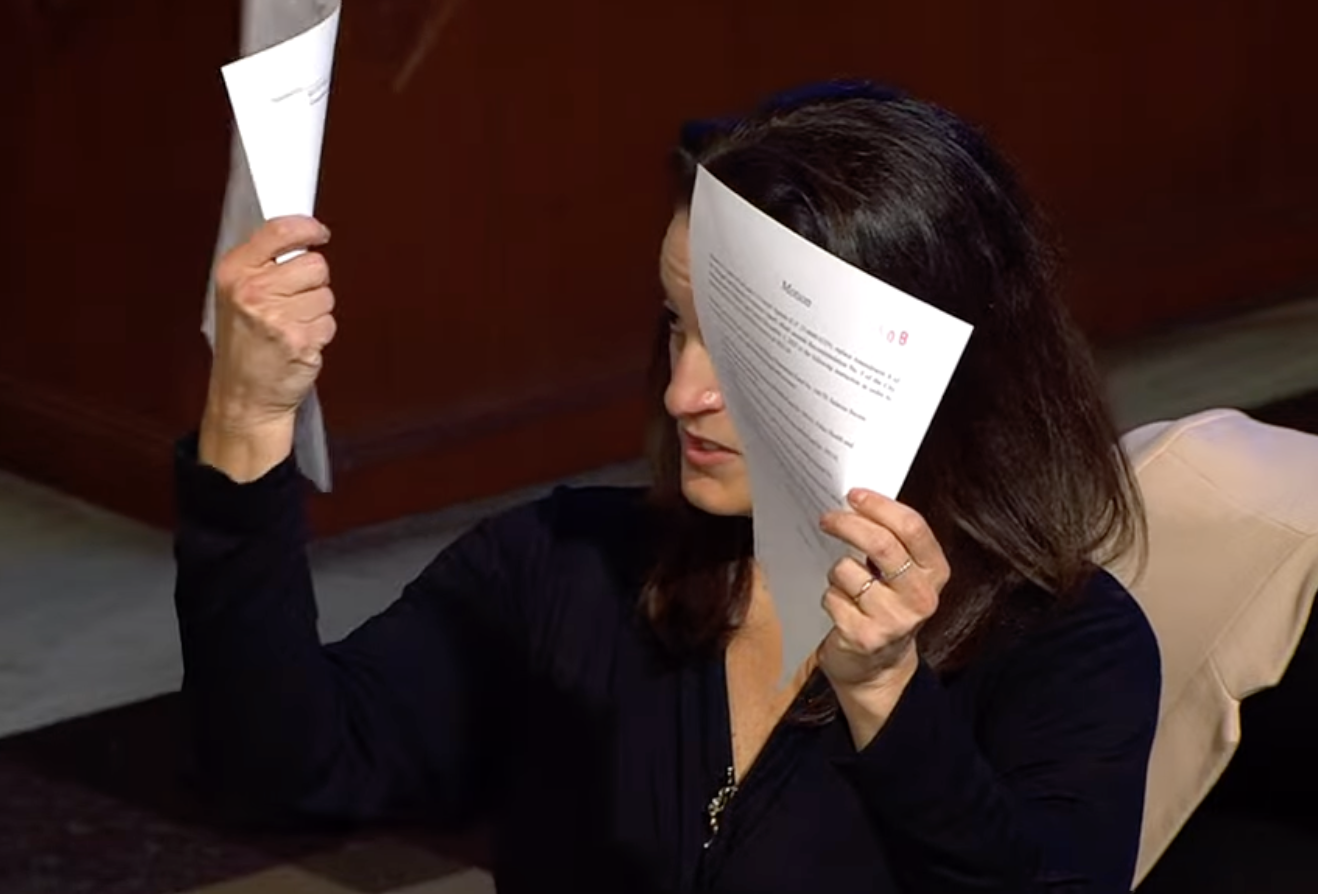

With the item split, Councilmember Katy Yaroslavsky made the pivotal procedural move. She substituted her language into the operative amendment and withdrew the competing amendment entirely. The effect was decisive. Council would no longer vote on approving the full amount LAPD had requested, roughly $4.4 million tied to accelerated hiring. Instead, members were steered toward a narrower package covering only short-term hiring costs, roughly $1 to $1.8 million, with the larger question deferred.

A procedural vote to accept that substitution passed. When Lee attempted to restore his original amendment and put the full funding amount back on the table, that effort failed. Although the amendment still bore his name, it no longer reflected his position, and Lee warned colleagues that rejecting the amended package altogether would leave LAPD with no funding at all.

That framing was reinforced by Councilmember Bob Blumenfield, who cautioned members that a no vote meant no money moving forward. Accountability was recast as recklessness. The choice presented was no longer whether LAPD should be rewarded for exceeding the budget, but whether Council was willing to risk disruption by refusing to clean up the overrun.

This pressure did not come from Council alone. Earlier in the process, LAPD Chief Jim McDonnell delivered a stark warning that hovered over the debate. “If you knew what I know about potential threats in the upcoming years,” he told Council, “we wouldn’t be having this conversation right now.” The statement offered no specifics and no public evidence. But it reinforced the familiar logic that whatever the budget says and whatever Council approved months earlier, police funding must be treated as an emergency exception.

When Council reached the substantive adoption votes, Councilmembers Eunisses Hernandez, Nithya Raman, and Hugo Soto-Martinez voted no, refusing to advance funding for a department that had disregarded the budget Council itself had passed. Hernandez and Soto-Martinez held that position through the final vote, but Raman’s record was more nuanced. She voted no while Council was still deciding whether to advance LAPD funding at all, placing her opposition on the record when the decision still carried substance. Only after the full funding proposal had been defeated and the vote narrowed to a temporary allocation did she vote yes, declining to use a final procedural vote to re-litigate an outcome that was already locked in.

The final approval passed overwhelmingly. LAPD received the reduced funding and a department that “went rogue” was made whole, at least for now.

What makes Item 40 disturbing is not just the outcome, but the process that produced it. Amendments were rewritten on the fly, motions bearing one councilmember’s name no longer reflected their position, and votes labeled procedural carried enormous substantive consequences. Even councilmembers repeatedly asked for clarification about what language was live and what had been removed. For the public, meaningful participation was impossible.

City Controller Kenneth Mejia has repeatedly warned that Los Angeles has a habit of finding money for police even when the budget says there is none. Programs addressing homelessness, tenant protections, street repair, unarmed crisis response, and basic services are told to wait or come back later. When LAPD overspends, the money magically appears.

Item 40 put that dynamic on full display. The budget was treated not as a binding democratic decision, but as a suggestion that could be overridden when police leadership and the mayor signaled urgency. By the end of the night, City Council had once again shown how fragile democratic governance becomes when policing is involved. When departments can ignore the budget without consequence and elected officials are asked to simply ratify decisions by the mayor, the budget is no longer a tool of democracy, but an after-the-fact justification for power.